Click on the title of a publication below to access the full text.

“Finding Their Purpose in Life”

50 Give or Take, May 9, 2025

50 Give or Take, May 9, 2025

A pastor and social activist for his lifetime, he lifted up the beauty of lives in need of peace. His son, a bartender, was his strongest supporter. They liked to say they did the same work: one works with matters of the spirit, one with matters of the spirits.

“Prison Tats”

50 Give or Take, Spring 2025

50 Give or Take, Spring 2025

To be published August 2025

“Tabletop Portraits and a Lifetime Together”

The Dewdrop, August 2024

The Dewdrop, August 2024

It was not immediately apparent to me what he was doing with the salt, but I had a clear, if inexplicable reaction as I watched. We were seated in the Pasand, an Indian restaurant in Berkeley waiting for our food. We were learning to know each other and every day something popped up to surprise and delight me. Across the table, Doug sat hunched over, absorbed in manipulating the grains of salt with his fingertips. He didn’t look up when the waiter approached, took no notice of the barking dog tied to the post outside the window, didn’t even seem to remember my presence. My reaction was palpable, as my heart slowed and I held my breath.

We weren’t sure yet what we wanted from this relationship. We were having fun together as we tried to figure out our own life paths. I had moved to Oakland to be near him after college, so we must have hoped for something. I knew I wanted us to be friends. He drew me here, but when I arrived, the liveliness of the East Bay was as attractive as he was. It was all new, exotic, and inviting. This was a place where strangers said hello and greeted each other at bus stops. It didn’t fit my stereotype of city life. Someone would say hi. Someone else would comment on President Reagan’s latest problematic policy. Everyone else would add their assessment, and continue with small talk about the weather or the latest movie. This was a community on a par with that of any small town of the Midwest where I came from.

I loved how the warmth of the Bay Area sun could make you shed your sweater one minute and seconds later let you shiver when you stepped into the shade. There were coffee shops in abundance, the cafes only served fresh-squeezed orange juice, never frozen, and cheap ethnic food of all varieties was available on every street. I tasted my first agua, my first korma, my first falafel. Walking down the sidewalk, one might see Lawrence Ferlinghetti (we did) and in the evenings we listened to the poet Alta read her poetry or heard Toni Morrison read from her new novel, Beloved. The street performers outdid themselves: the polka-dot man, the guy crooning 1930s love songs with a child’s plastic microphone and amplifier, the bearded crossdresser in fishnet stockings and high heels. Every rush hour, one old man stood in the median strip of Martin Luther King Boulevard waving a cheery hello to passersby.

I came to this place to explore a potential relationship, then found myself also falling in love with the energy of this East Bay city. Doug’s LP of Phoebe Snow singing “Walkin’ with my baby down by the San Francisco Bay,” struck a chord deep within. I was unexpectedly, immediately at home in this new world, a place where even the sunlight was a different color, or so it seemed.

Doug’s apartment was a southwest-style, efficiency row house on a narrow Oakland street. His neighbors were aging Hell’s Angels who took it upon themselves to care for the senile old woman on the street who had no family. They invited us over for cherry pie and helped fix Doug’s car. Like everything about the Bay Area, they defied stereotypes and allayed any residual fear I harbored.

When Doug got home from work, he would spend the first half hour walking back and forth across his apartment, playing haunting melodies on a wooden Japanese flute. He did this, he said, to get psychologically prepared for the evening, to decompress and transition between two worlds. Retail electronics was not a job that fit his psyche. Interacting with the world always stressed him. His dream, he told me, was to live in a cave in the mountains and heave rocks at anyone who came close. He found small talk painful, and preferred to be an observer rather than a participant. He analyzed, theorized, and pontificated about the world’s imperfections. He found its flaws difficult to face, but he was even less tolerant of his own inability to create a better society for others.

Some evenings he made us elaborate vegetarian meals of asparagus crepes or grilled tofu and veggies, making each item with slow deliberate precision. If dinner was at 10 because of his precision, who cared? We were in our twenties, full of energy, and our time was limitless. But, honestly, I wasn’t used to long transitions or interminable waits. I wanted action, spontaneity, exploration.

When he didn’t want to cook, we often found our way to The Pasand, a restaurant that served large quantities of southern Indian food for a mere pittance. Its Masala Dosa could easily satisfy two underemployed people. The service was notoriously poor and a few years later the place came to be known for its egregious labor practices (people began to call it “Slaves-R-Us”), but at the time all we knew was that the food was tasty and we weren’t in a hurry.

It was in the Pasand where I first watched Doug create his fleeting works of tabletop salt art. His creations, as I came to see them over the course of a year, were exquisite. But it was the process itself that gave me the spine tingles, that clarified in part, how I felt about him. It was in the way he moved the grains with his fingertips, in his absorption in his work, even in the way I was momentarily not part of his internal world. This was all part of getting to know him and part of determining just how much effort I wanted to put into this thing that was happening between us.

That first time, I didn’t know that I would watch this process numerous times over the coming year as we waited for our food, sometimes with friends, sometimes just the two of us. I only knew that I was a little embarrassed as he emptied the saltshaker onto the table. I looked around to see if his mess would attract the attention of the waiter or a manager. In the world in which I grew up, one did not waste food, not even salt. In his concentration, Doug didn’t notice my consternation. He just manipulated the grains carefully, deep in his own inner space. It took a few minutes to realize that his mess was not random. Each movement of his fingers rearranged so little and yet, slowly I began to see a figure taking shape in the grains on the table.

Several waiters stopped to watch, too. The food came and I motioned for it to be placed at the other side of the table. We all waited quietly, afraid to break the spell. As I watched a picture emerge, the ancient text slid through my thoughts: “You are the salt of the earth.”

When Doug finally raised his head and sat back in his chair, we moved around to stand behind him. There, etched in the white salt, contrasting against the darkness of the tabletop, was the face of Richard Nixon, jowls and all. The spell was broken, and everyone laughed. After all that reverence and expectation, this was the last thing we expected.

“Look quick,” Doug said. “Art doesn’t last forever.” As the waiter walked away, Doug swept the grains of sand into his hand and added, “This art belongs on the potatoes.” He sprinkled a few grains over our Masala Dosa, then poured the rest of the salt into the potted plastic plant that stood beside our table.

It’s been forty years and Doug and I are now entering retirement together. Even now I’m learning new things about him. His flute has been dormant for the last 20 years, but I often go to sleep listening to him play piano in the next room. His salt drawings are a thing of the far distant past. Some days we are, I fear, far too wrapped up in the mundane aspects of life: how to xeriscape the lawn, keeping track of doctor’s appointments, which electric car to buy and how many extra solar panels that will require.

And then I remember those salt drawings and how they made time appear to stand still while restaurant life swirled around us. Now they say “pics or it didn’t happen,” something that would have made no sense in the days of film-based photography. Today, I would have a series of snapshots on my phone to text to friends or post on Instagram. But I don’t have the pics and still I know it happened. I have my memory of those first glorious years when we lived in Oakland, how we struggled through the beginning of a relationship, how I was mesmerized by some simple temporary salt drawings, and how we believed we had all the time in the world to figure things out.

www.thedewdrop.org

“The Last Laugh: A Love Story”

Beyond Words Literary Magazine, August 2024

Beyond Words Literary Magazine, August 2024

When I am dead, my dearest, Sing no sad songs for me ... -Christina Rosetti

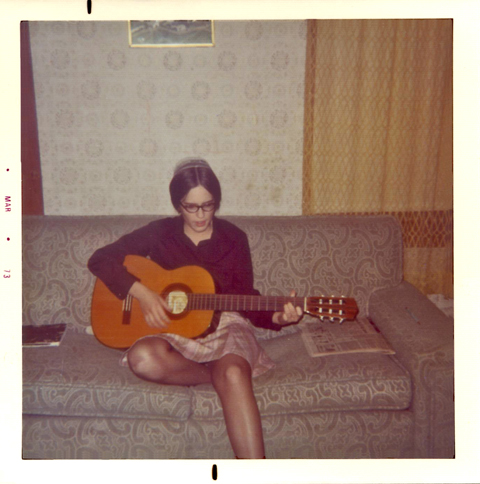

In the summer of 1973, sandwiched between our junior and senior year of high school, our job was mowing our church’s cemetery weekly. It was just Joelle and me, guiding two old push mowers around an acre of gravestones in the stifling midwestern summer heat. By the second week, we were sick of the humidity and exhausted by acres of mowing and trimming. We were, however, happy for some spending money, for the satisfaction of getting a job that they usually gave to the boys, and for the fun we had working together.

Carefully we mowed and trimmed around graves proclaiming deaths as old as a hundred years and as recent as this summer. Some names I knew: my grandpa, a great uncle, the old woman who gave me candy on Sunday morning when my mother wasn’t looking. The gravestone of the old woman reminded me of Sunday mornings sitting on the wooden church bench beside her, waiting for her to open her big black purse and pull out the striped Neapolitan Coconut Bars she stowed there.

Most graves were long covered over with green grass, but one was still bare dirt heaped atop a newly-dug grave. This mound covered the body of a boy our age who had died in a plane crash that spring, a disquieting reminder that, despite our youthful hopes and delusions, we were not immortal.

We stopped frequently to rest under a hickory tree, to drink ice water or lemonade, and to talk. The job was monotonous and the heat was suffocating. Regardless, we laughed a lot—at ourselves, at our community, and at the world around us. In these moments of rest, we shared places we wanted to see, things we hoped to experience. Our future seemed promising enough, better than these boring, stressful high school days.

On one break, late that summer when the temperature hovered near 100, Joelle sat up and stared at me with her characteristic forcefulness. “I want you to promise me something.”

I picked at the weeds, put a blade of jimson grass between my thumbs and blew a shrill whistle before responding. I knew how to hold her intensity at arm’s length. “Okay. But I need to know what it is before I promise.”

“Promise me first,” she said.

“Not going to happen.” I was determined to hold out.

She must have heard my edge, because for once, she didn’t insist. “Someday, wherever you are when you hear that I’m dead, I want you to laugh.”

I looked at her and started to laugh, but she stopped me. “I’m. Dead. Serious. I need to know that someone will laugh when I die.” I told her that people would think I’m crazy if I laughed at her funeral, but she shrugged. “Why would you care? It’s what I want.”

We entered our senior year that fall, followed the Watergate hearings closely, attended our high school’s basketball games across the state. We studied, partied and prayed with our youth group, and went to the Junior-Senior Banquet together. We were the wallflowers of our high school, but we laughed at everything. That’s what I remember most—the never-ending laughter. In the spring, we graduated from high school, ready to move on. When I thought of my future, I thought that no matter where I ended up, Joelle would be nearby. We never discussed her request again.

For several years, we kept touch. I was Maid of Honor at her wedding. She moved to Texas, married a minister, and began having kids. I was restless and moved around the country for a few years before starting classes at the university. By then, we had stopped writing letters, stopped timing our visits home to coincide. Our lives had gone in decidedly different directions.

I have not yet heard that she died. I wonder sometimes if she remembers what she made me promise that long-ago summer. I haven’t forgotten. For years I wondered how I’ll feel when I find out that she has taken her last breath.

With the passing of years, I don’t wonder anymore if I will be able to fulfill her wish. I will laugh. And when I laugh, I will be remembering that lazy summer afternoon so long ago when we chatted in the shade of the hickory trees between rounds mowing the cemetery. I will be thinking about the fun we shared even though we didn’t quite fit in anywhere. And I will laugh in gratitude for this memory of my once-upon-a-time best friend who just wanted to know that someone will laugh when she dies.

https://www.beyondwordsmag.com/

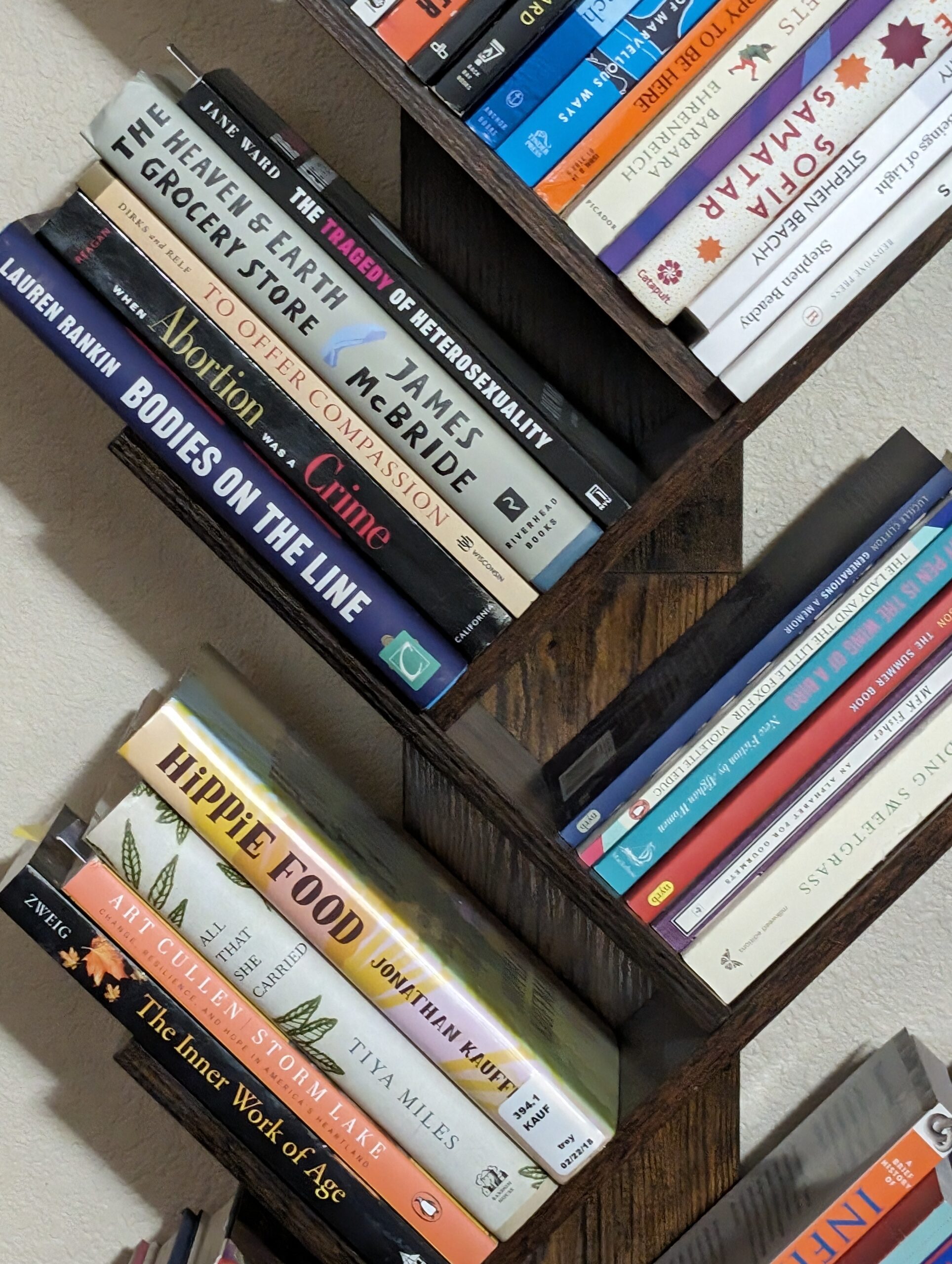

“The Things She Read”

Greenlight Magazine, Spring 2024

Greenlight Magazine, Spring 2024

All her life she had believed in something more,

in the mystery that shape-shifted at the edge of her senses.

–Eowyn Ivey, in The Snow Child

Learning to read was a bit of a rush for the sheltered sensitivities of one five-year old Mennonite farm girl. It fanned within her the flames of adventure, the hidden secrets of empathy, the heady power of words. Even the simplified lives and stilted dialogue of Dick, Jane, and Sally were windows into unknown worlds. She read and re-read The Girl with Seven Names and Thee Hannah. It was years before she understood the historical milieu of these young Quaker girls. She just knew that she loved their spunkiness and identified with Hannah’s dislike of her bonnet.

She made short work of the books in the libraries of home, one-room country school, and church. Their small-town library was a single room in an abandoned store front ten miles from home. Her parents bought what books they could afford, both classical and Christian kid’s lit, books like Tom Sawyer, Call It Courage, and The Sugarcreek Gang. She was particularly fond of any book where children romped across meadows, waded in streams, explored forests, or rowed across small ponds or ocean inlets. Adventure and travel were an integral part of her literary appetite, while in real life she hated all things with weeds, bugs, water, or boats. Truth be told, she harbored an inordinate fear of drowning, but she loved to read about children who knew how to maneuver a scow, skiff, or canoe. Getting lost (and then found) in wilderness or cave provided all the requisite shivers and ecstasy of a horror story.

She gravitated toward Frank and Joe Hardy; they could, it seemed, get just a bit dirtier and run a little wilder than Nancy and George. The same held true with Little Women and Little Men. She fancied herself a detective with Encyclopedia Brown, an inventor with Alvin Fernald, and a writer/adventurer with Henry Reed. If a book included a map she was hooked. The best way to beat the oppressive mugginess of an Iowa summer was to lie on a blanket in the lawn, dreaming of adventures in forest, swamp, or haunted house while brushing off ants and watching out for the ubiquitous garter snakes.

In second grade, she left the comfort of her one-room schoolhouse for a long bus ride to town, which gave her more time to read. Her favorite time of the month was the arrival of the Scholastic Book Club list when she could purchase small, poorly-bound paperbacks for a dime or a quarter. She counted each penny from her weekly allowance and bought as many as possible. The newsprint booklist was in shreds long before she placed her order. She mostly bought biographies, and the lives of famous people unfolded before her: Helen Keller, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr.

In junior high, her best friend gave her copies of Catcher in the Rye and Catch 22, which held her captive, “blew her mind.” Her high school English teacher introduced her to Carson McCullers and she hunkered down in lonely isolation alongside Frankie Adams. Literature became more than a mystery or an adventure. It held her hand through an extended period of adolescent depression and identity crisis. At her older brother’s college apartment, she read thick tomes about the Kent State massacre and the Vietnam War.

She dreamed about college but was convinced she wasn’t smart enough. Plus, she didn’t want to teach or become a nurse or a social worker, and what else was open to a girl? While wandering through a local used bookstore, she and her cousin picked up Our Bodies, Ourselves and found pleasure with the aid of her new-found knowledge—and mirrors. During a backpacking trip across Europe with this same cousin, she read Kurt Vonnegut and Bertrand Russell on the recommendation of her cousin’s boyfriend. Questions began to solidify in her mind.

When she returned home, she squelched her self-doubts and enrolled at the state university to study history and religion. Her professors assigned Siddartha and The Immense Journey, Kafka and Potok, Tillich and Kierkegaard. As she had been enlightened about her body, she was now tuning in to alternate world views. When her history professor taught herstory, (while battling obnoxious boys unwilling to learn from a woman) she discovered Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells Barnett, Rosie the Riveter, Rani Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi, and The Feminine Mystique.

A friend suggested that she lighten up and read more novels, so she turned to The Color Purple, Toni Morrison, Martha Quest, and John Irving, while continuing to read Adrienne Rich and Gerda Lerner. She walked in Take Back the Night rallies and anti-nuclear marches; she attended conferences on women and society; she sat topless in the sun with friends at women’s concerts. She pondered every lyric ever written and sung by Ferron.

When friends’ bookshelves began to include What to Expect When You Are Expecting, she pursued a graduate history degree, perusing Joan Scott, Jill Ker Conway, and John Hope Franklin. She was nearly forty before becoming the mother of two pre-teenagers, when she immersed herself in The Primal Wound. Over the following decade, all she time for were books on bipolar disorder as she navigated the rough waters of her daughter’s adolescence. When late-night worries hampered sleep, she searched for momentary solace in The Bean Trees, then further depressed herself with Backlash, while wondering where her ideals and her life had gone. Through all of it she steered clear of those ubiquitous self-help books which, quite frankly, simply irritated her.

When space finally opened up to read for pleasure, she was saddened to find that she fell asleep far too quickly, which did nothing to shrink the tower of books teetering by her bed. She laughed at the world with Anne Lamott, was motivated into action by Half the Sky. She and her husband began to read the American classics of literature together, something both had missed in their early education: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Updike. She quickly concluded she had not missed all that much and returned to writers who she, quite frankly, found more stimulating, authors like Miriam Toews or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi.

At sixty she became a precinct coordinator, began to register voters, and worked on local congressional campaigns while reading Timothy Snyder, Rebecca Solnit, and Dahlia Litwick. But at night she retreated into her bedroom to lay down beside her stack of novels. She knew she’d never get to them all, but their mere presence gave her a feeling of hope and moments of contentment, aided by the calm meandering of Alice Munro stories.

Then one day, she began a search for some of her childhood favorites, savoring stories with the comfort of memory. She longed to lie down in the backyard again, doing battle with the ants while paddling a dory across an imaginary cove, oblivious to the world beyond her front door. All told, however, she was happy to be here in retirement, a time when she hoped to be able to read any hour of the day, while registering voters in her spare time.

By this time, she had learned that she’d never finish every book, climb every mountain, or solve all the world’s problems, but she also came to recognize how little it mattered, or rather, she began to understand what mattered most. As an old woman, she would choose her books, her mountains, and her battles carefully, as long as her mind, her eyes, and her legs hold out.

“A Mennonite Woman in ‘Thanksgiving Town’: The Employment of Edith Swartzendruber, 1935-1941”

Labor’s Heritage, v.3, #1, Winter 1991

Labor’s Heritage, v.3, #1, Winter 1991

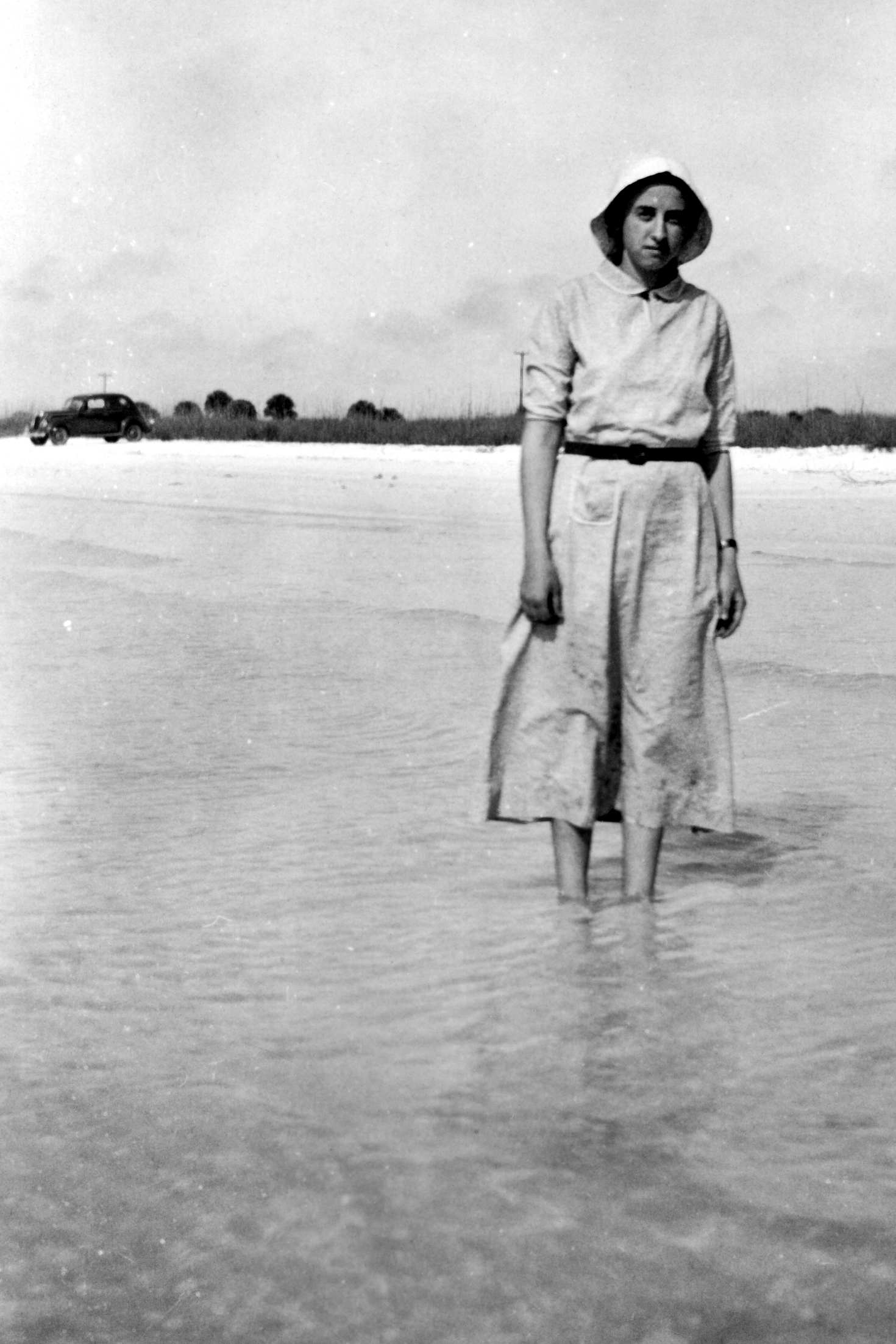

Edith Swartzendruber Nisly was born in 1919 to Elmer and Mary Bender Swartzendruber on a farm near Wellman, a small town in southeastern Iowa. The family had lived in the area since the 1850s, when her great grandparents settled there to farm and raise a family. Her great-grandfather became minister of the first Amish Mennonite congregation officially organized in the area. In the decades to follow the Swartzendrubers maintained close ties to farm and church, but Edith encountered an influence that ultimately caused her to see the non-Mennonite world differently than her parents or earlier generations viewed it. In the mid-1930s she took a job at a small turkey processing factory, an employment experience that altered her perceptions but did not change her values. What follows is a narrative by Edith’s daughter of that work experience.

Edith’s father served as a minister in this growing, tightly-knit Mennonite community. By the 1920s and 1930s there were five Mennonite churches in the area and a total of 1000 to 1500 members. Upper Deer Creek Mennonite Church, where Edith worshiped with her family, had a weekly attendance of around 300 people. These people not only worshipped together but they sent their children to the same public schools nearby, they conducted their business with each other as much as possible and they socialized with each other. In the first decades of the twentieth century, when transportation limited mobility and church beliefs called for strong community ties, the lives of the Mennonites of rural Wellman, Iowa, were closely interrelated. Church, school and family consisted mainly of the same people. In addition, they retained the German vernacular and conducted church services in that language until nearly 1940.

Mennonites believed in a strong sense of community. Salvation was closely tied to the life of the church and its members as they made decisions together throughout their lives. They intended to live this community life separate from the world, most notably through non-resistance and nonconformity. Non-resistance meant several things to Mennonites. First and foremost, it indicated that they would not take part in any war, that life rather than death was the business of the church. It was also a part of their everyday lives through peaceful interpersonal relationships. Nonconformity also had several facets. The most readily apparent was a distinctive mode of dress. The church felt that its members should dress plainly and simply. Women wore long dresses and white prayer veilings over their hair. Men shunned ties. Both men and women wore subdued colors. More than an issue of morality, clothing signified humility in a world of pride, promoted uniformity within the church and helped to maintain a separation from the world. Nonconformity also meant a lifestyle that eschewed the accumulation of material goods, embraced a simple form of life and level of consumption and promoted honesty in business transactions.

In 1933 when Edith was fourteen and ready to graduate from the eighth grade, she encountered an obstacle in the form of an unwritten but firm church belief that forbade high school attendance. Education, the church felt, was unnecessary and would draw young people away from the church and the community. Edith loved school and did not want to quit. Her parents, particularly her father who had longed to go to college, disagreed with the church’s views on education but as the minister’s family, they felt a need to acquiesce in the congregation’s desires. Edith and her parents agreed that she would attend high school for one year, a compromise discouraged by the church but one that it grudgingly allowed. At the end of the school year in 1934, Edith finished her studies and began her work life.

The years of the depression touched this rural community, but apparently not to the extent that they affected much of the rest of the United States. The Swartzendrubers lived on the farm that had belonged to the family for several generations. They had land on which to grow crops and food to put on their table in much the same way that they had done in previous years. Edith remembers their large garden that they maintained every summer: “I think it was one of my mother’s aims to have a clean garden because I know we hoed and hoed and kept it clean, kept it so that it produced well. And we not only planted a few things. We planted enough potatoes for the winter and enough sweet corn and peas and beans and beats and everything.” The family never lacked a variety of fruits and vegetables. In addition to the garden they had an orchard and berry patch that produced cherries, peaches, plums, apples, grapes, strawberries, raspberries and blackberries.

A source of income for those years was a family milk business begun in the early 1930s. The Swartzendruber family had cows but at the time there was only a market for the cream; so they began to make chocolate milk, bottle it, and sell it in Wellman. In assembly line fashion, the entire family helped in this enterprise. One of them mixed the milk and chocolate while the others filled, capped, and cased the jars. Edith’s father made a motorized bottle scrubber and capper to facilitate the process, and they maintained a thriving business for a number of years. Every weekday during the summer months, they filled six to eight cases, each containing twenty-four bottles, put them on ice and hauled them to town to sell to the grocery store, the creamery, and to several other businesses that kept milk to sell much as many places have soda machines today.

In addition to farm work, Edith’s mother had organized and was now head of the church sewing circle. Mary and her daughters spent many hours preparing quilts and clothes for the monthly meeting, items that were sent to the Mennonite Central Committee to be used in worldwide relief work. “We cut a lot of garments, made a lot of dresses. We would have them all cut out at home before we ever went to the sewing [circle meeting] so they were ready to work on. That responsibility came to the one who was in charge and [Mother] was in charge a lot of the time. I well remember spending days doing nothing but cutting clothes.”

The year of 1935 was a pivotal one for the family. The birth of the seventh and last child and the marriage of the eldest daughter occurred. In addition, some family members sought employment outside the farm environment: the three oldest daughters at the Maplecrest Processing Plant and their brother, Morris, at the Kalona Oil Company where he delivered fuel oil.

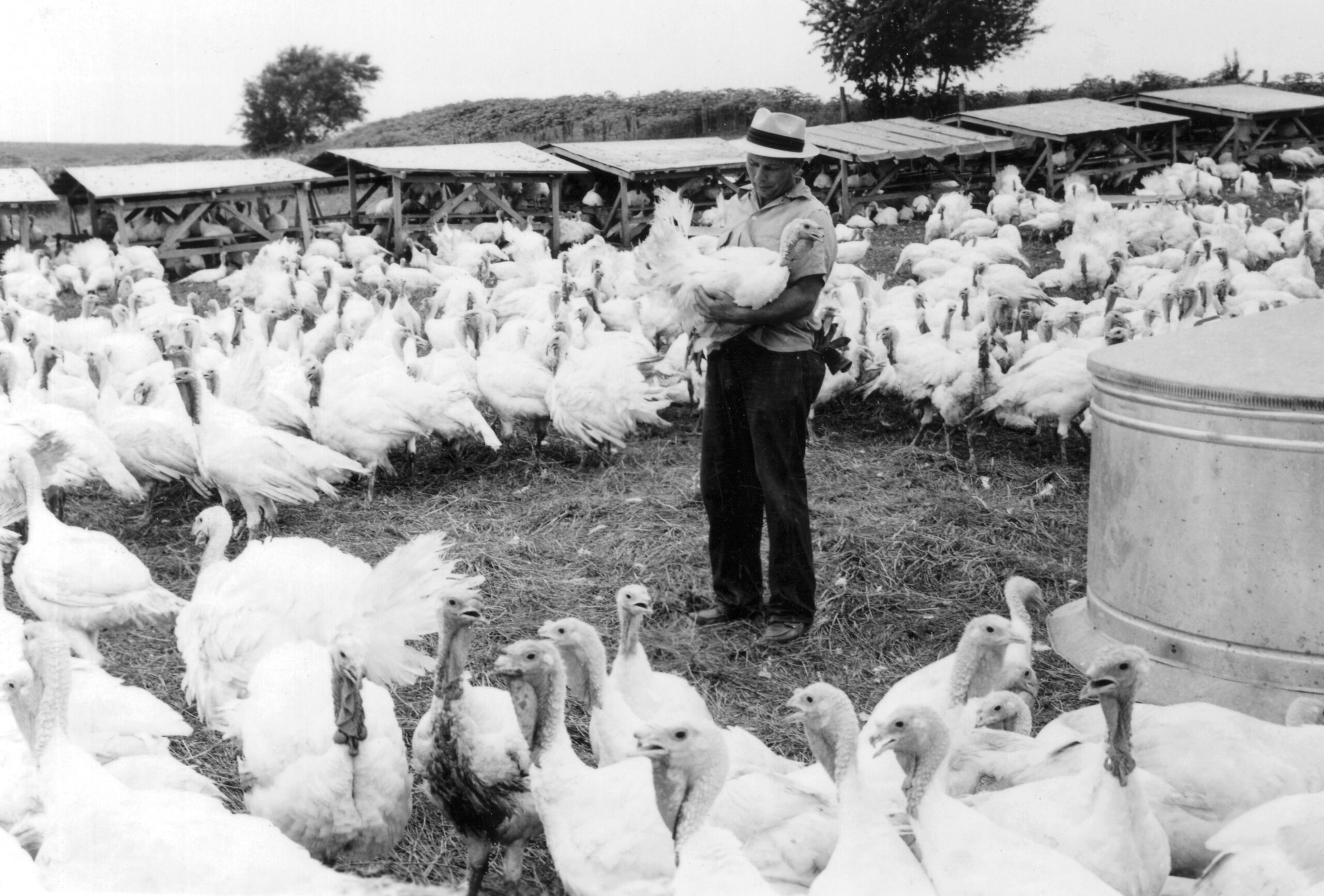

In 1928 A. C. Gingerich founded the Maplecrest Turkey Hatchery on his farm that bordered on the Swartzendruber family farm. By 1935 many of the local farmers had begun to raise turkeys for Maplecrest, and the operation outgrew its farm beginnings. Gingerich built a processing plant in Wellman and expanded his operation from hatching turkeys to dressing them for market. A special spur line ran from the railroad to the loading dock. After workers dressed the turkeys, they loaded the birds onto freezer cars and sent them to New York, Chicago, Cleveland and other cities. The business brought much needed jobs to Wellman, and between 1930 and 1939 the population grew thirty-two percent, largely due to the new labor force. The town came to be known as the turkey capital of the United States and was often called “Thanksgiving Town” or “Turkey Town.”1

If the people needed jobs, so too, Maplecrest needed the workers and it was a simple matter to get employment. One only had to walk in and ask for a job. In the fall of 1935, Edith, her older sisters, Mildred and Effie, and her mother’s half-sister, Fannie Bender, were among those who sought work preparing the turkeys for market.

The acceptable and available means of earning money for them at that time was to find work in other Mennonite homes or as farm hands. The Swartzendruber children had seldom “worked out” previously. Their mother needed them to help with farm work during their father’s frequent travels across midwestern and mid-Atlantic states on church-related business. Prior to 1935, Effie was the only daughter who had worked away from home, serving as a hired girl in the home of a neighboring Mennonite family.

Despite the fact that Edith and her sisters had not worked away from home before, the decision to do so was not a particularly difficult one. The owner of Maplecrest, A. C. Gingerich, was a longtime friend of Edith’s father, Elmer. They had grown up together, attended the same school and played on the same baseball team. The Gingerich family belonged to another Mennonite church in the area. Even though the number of Mennonites working at Maplecrest was never more than fifteen to twenty percent of the total, going to work there, in at least one sense, did not make the Swartzendruber sisters feel like they were leaving the community. Edith recalled, “I wanted to go. I had never done anything like that before and I had company to do it so I wasn’t afraid to start something new.”

Turkeys were only in seasonal demand in the 1930s and the job was, therefore, available only in the fall of the year. “Thanksgiving Town” was an appropriate name for the town that was home to this new industry. From late September until Christmas the plant was the scene of furious activity: “Turkey was a holiday bird. It was not a year round meat like it is now. Most of the sales were over Thanksgiving and Christmas.” During the season, Sundays and Thanksgiving Day were the only times the plant closed. As Thanksgiving and Christmas approached, the work slowed down. “They tried to have them [the turkeys] all out of the fields before Christmas,” Edith explains, “They weren’t prepared to handle water and feed in cold weather, when it was below zero.”

Coming when it did, Edith’s new job conflicted with farm work. “Of course we had to chore and we had to go out and husk corn by hand in the fall,” Edith remembers, “so we couldn’t always go to work because corn husking was in October too. If you couldn’t go [to work] you just didn’t go…If there were rainy days, we would go to [Maplecrest] and then would husk corn in between.” Sometime in the 1930s the family bought a corn picker which lightened the load but did not remove the need for farm hands. The children still had to help at harvest time. Workers could choose when to report to work at Maplecrest dependent on when their parents needed them for farm work.

Work at Maplecrest usually commenced at 6:00 a. m., but prior to that hour the three young women had other tasks to complete. They were often up before 5:00 a. m. to milk the cows before leaving home on their seven mile trip to work in Wellman. The days were long and the work tiring. The length of the workday varied according to the number of turkeys that came in with any given batch. Maplecrest contracted with farmers who took the turkeys in the spring and raised them for the company. In the fall, Maplecrest sent people to these farms to inspect the turkeys and to determine when they were ready to be butchered. They then would send trucks to load and bring them to the plant.

As Edith recalls the workday, “We sometimes worked from six o’clock in the morning until nine at night until they had the bunch filled that were there that they had hauled in because the season was so short. The trucks would come in and we had to finish the truck. We couldn’t let them on the truck overnight. So we worked long days and were tired.” The size of the flocks varied from 2000 to 3000 birds. The company typically knew how many turkeys would be coming in and informed its employees how long they could expect to work the following day.

Preparing the turkeys for market involved several steps. The first thing that needed to be done was to unload the trucks. After that the turkeys were hung on a moving chain and several employees killed them by sticking them in the necks. The turkeys then were put through scalding water to rough their feathers in preparation for removal. A hot wax bath came next followed by a dip into cold water to set the wax. After the wax machine, several more people broke the wax, a process that removed most of the feathers. The last step prior to packing and shipping required removing the fine pinfeathers that remained. The turkeys were “New York-dressed” meaning that they were killed and cleaned but the heads were left on and they were not gutted. They were frozen immediately and shipped this way.

Edith and most of the female employees were involved in the process of removing the fine pinfeathers, what they referred to as “pinning” the turkeys. The birds hung by their legs every two feet on a chain that moved them slowly back and forth around the room until they reached an inspector and the packers. The women would start pinning the turkeys and move along with them around the room until they had completed the task. For this task, the company paid them on a piecework basis, approximately three or four cents per bird. Edith recalls that when they worked fast enough “a lot of us could make as much as, oh, maybe thirty or forty cents an hour and that was good, good wages at that time, for that period. So you really liked to work there.”

The excitement of a new job quickly wore off. The women were walking constantly and reaching up to complete their task. “it was a pretty tiresome job and the days got long and tiring. It was a little boring because it was the same thing over and over all day long.” Turkeys hung with their heads down and blood continually dripped on the women. Sometimes it was easy to pick out the pinfeathers or there were few left after the wax was removed. As often as not, however, it was difficult for the women to finish the task. They used blunt knives to pull out the pinfeathers, but they were not supposed to scrape the turkeys. Birds that were scraped became dark and discolored when they were frozen.

When each woman finished pinning a turkey, she then moved back to the beginning of the line to pin another bird. Edith recalls the strenuous process:

We followed and tried…to get them as close to the wax fellows as you could cause then you had all this distance and if you got done [before the line ended at the inspection point] you could go back and get another one. But if you didn’t get done…you had to follow it all the way around. It didn’t go fast. It was a long way. And you continually worked at least at eye level. The legs would have been higher than our head a little bit. We were working above our head and down on this turkey to its neck since it was hanging by its feet.

The women wore large rubber aprons to protect themselves from the dripping blood. Each of the women was assigned a number and in her apron pocket carried numbered tags to place on the turkeys when she pinned them. After turkeys passed inspection, another woman removed the tags and tallied the number of birds each woman pinned. When a turkey did not satisfy the inspector, that person called out the tag number and hung the turkey on a side rack. The woman who had worked on the bird was expected to return and bring the turkey up to the required standards.

Maplecrest halted the work to accommodate a half hour lunch break. The company operated a lunch counter on the second floor of its building, but Edith and her sisters usually carried their lunch from home. There were no other specified breaks in the day; however, employees were free to take additional breaks if necessary: “When we wanted to go to the rest room or something we just went. And if you wanted to take a little more time out you just lost more turkeys.”

Discipline appears to have been relatively lax. Edith remembers, “The foreman wasn’t standing over us. You could take breaks. You just took them on your own time because you weren’t pinning. When you worked by the piece, if you weren’t working you weren’t making anything either. I don’t remember that they ever got on us for anything.”

Occasionally, the women were given a rest from the job when the trucks were late delivering the next batch of turkeys.

Sometimes we had to wait on the trucks and then it would run into the evening. While we waited we were not getting any money since we were being paid by the bird. We would usually wait up in the restaurant. You couldn’t go far away because you never knew when the truck would come and the chain would start….We were just glad for a chance to sit down because the rest of the time we were walking continually following the chain around to pin the turkey. We got tired but we were young.

The company allowed the women additional reprieve when a batch of turkeys came through that was particularly difficult to pin. When that happened the foreman stopped the chain giving the women time to catch up before more turkeys came down the line. At other times when they did not finish a turkey before the inspection point, they had to hang it on a side rack to complete it before hanging it back on the main chain for inspection.

The men who worked at Maplecrest completed tasks that required lifting. The turkeys were large, between eighteen and thirty-five pounds. Men unloaded the trucks, hung the birds on chains, killed them and removed the wax. After the pinning process, women inspected them, and men took them from the chain and packed and loaded them in the freezer. In addition. To the jobs of pinning turkeys or removing and tallying the tags, women also worked in the lunchroom and the office. The office workers, whose jobs were year-round, did the bookkeeping and secretarial work.

The job in Wellman brought the young Mennonite women into contact with people and a way of life that they had not seen before. There was only a small group of Mennonite women who joined this work force and for the most part they did not mingle with the others. The differences were obvious due to distinct Mennonite dress and hair styles, and the distance between the groups was not easily narrowed. For the most part relationships were good while not intimate, but there was occasional antagonistic behavior directed at the Mennonites. For example, a few women from town learned that they could take advantage of the Mennonite women. Edith recalls:

We often got the bad deals….They would watch and if there was a real pinny [difficult] turkey on the chain they didn’t go until someone else went. And the rest of us, we finished then went and took whatever was there. We often got the bad ones and then you couldn’t make as much. But these other ladies who didn’t care, they made the most money.

Edith also remembers:

Another thing that some of those girls did…if they happened to have a bad turkey and you had a good one and you left, they sometimes switched your number on their turkey. You knew that when [the inspector called your number] that it was not a turkey that you would have left.

The Mennonite women never complained since their training at home and at church taught them to avoid disputes. They simply did their best to control who they worked beside and tried to get along without any conflict.

The environment which Edith and her sisters entered opened up a new world to them:

There was an awful lot of rough talking and swearing and stuff. I have wondered already how did the folks feel about us being in the type of environment we were in there because it was rough. A lot of the women smoked and that was a time when not a lot of women smoked. And that bathroom and the cloak room, we just didn’t sit in there very often because that was where they smoked and talked so ugly. And I sometimes thought that they probably talked worse, said nasty things and dirty stuff on purpose for our sake to see if they could shock us, see what we’d say.

As much as possible the different groups of women stayed away from each other.

The new contacts, however, were not all unpleasant ones. Edith also made friends with whom she maintained ties throughout the years. The women helped each other become accustomed to job procedures, teaching the newcomers as they arrived. No orientation existed except as they provided for each other. Years later one woman thanked Edith for helping her learn the job tasks:

She said I befriended her which I really don’t remember. She said I showed her how to go about it and get started and really appreciated it because she knew no one when she came in there to work, and she said I came and talked to her and took her with me to work….She said she always felt that I was a good friend of hers because of that.

While working outside the farm brought Edith in contact with the larger world, it did not make her independent of her family. She kept a small amount of money to buy a treat when she went to town, but most of her income helped her parents buy necessitites. Edith’s brothers and sisters also turned their wages over to the family:

I think that it was the understood thing by most people at the time that you gave most of your money home until you were twenty-one, but they bought what we needed or they gave us the money to buy what we needed. I didn’t have a new coat ever until the fall we got married. I always wore something that was handed down to me from one of the others. I was smaller so I naturally got them. I sometimes resented that. I would have liked to had something new once in awhile myself.

For seven years, from 1935 until 1941, Edith left the farm in the fall to earn money pinning turkeys at Maplecrest. Her days were spent working, her evenings, when she did not work late, at home with her family.

I make it sound as if we did nothing but work. We had things going in the evenings occasionally … a young people’s gathering of some kind … I guess I remember most the good evenings we had at home ofttimes reading and so forth during the wintertime when we weren’t’ so busy like it was in the fall. I well remember us sitting around the living room and everyone reading and doing what they wanted. Where nowadays if you have a family that will sit down in the evening together and each do their own thing in their own living room it would be a rarity. Sometimes we sang and sometimes we played games. We learned a lot of songs.

She and her brothers and sisters attended singing school and practiced shaped-note, a cappella singing at home in their spare time.

Saturday was a time to prepare for Sunday. When the children were not working at Maplecrest they cleaned and baked because, as the minister’s family, they almost always had Sunday guests. Even when they worked at Maplecrest, they usually could go home early on Saturday because the company tried to schedule fewer loads of turkeys. Saturday evening was always a time to study the Sunday School lesson, rest or memorize Bible verses in preparation for Sunday.

This pattern of fall work at Maplecrest was broken when Edith married William Nisly, a yojng Mennonite man from the same community. In 1935 he had arrived from Kansas, which his family fled after the dust storms had ruined their crops. The wheat yield had fallen from forty-five bushels to ten bushels per acre and it became impossible to support themselves. The family decided to move to another Mennonite community and chose Wellman. Once there, William also helped support his family by working at Maplecrest, where he packed turkeys into crates for shipping.

William and Edith married in November 1940. Edith worked a short time at the beginning of the turkey season that fall and then quit to prepare for her wedding. After the nuptials William went to Flint, Michigan, to pick up a new 1941 Chevrolet and deliver it to a dealer in Oregon. For their honeymoon, William and Edith drove the car to the West Coast and received travel expenses as compensation. They returned to Iowa and began to farm 125 acres that they bought from William’s parents. In the fall of 1941 Edith returned to Maplecrest for her final season of work there.

The war in Europe had begun, and in the fall of 1942, William left to join the Civilian Public Service (CPS), the Historic Peace Churches’ alternative to the draft.2 Because of his religious belief in non-resistance, William registered as a conscientious objector and worked as an orderly in a hospital rather than taking part in the war. When he left, William and Edith sold their farm, and Edith, now six months pregnant, went to live with her parents. She moved to northern Indiana in 1944 to be near William, who was working as an orderly in a Kalamazoo, Michigan, mental hospital. His CPS allowance was not enough to support the family so she worked for three months packing and shipping flower bulbs and plants at a nursery.

After the war, the Nisly family returned to Iowa and moved onto the Swartzendruber home place and resumed farming. From then until 1961, Edith’s work consisted of unpaid labor: raising eight children and running a home and farm. Her only connection to the poultry industry was the farm’s turkey flock. Of her six siblings, only she and one sister still lived on farms in 1950; only she remained on one in 1960. After 1961, Edith and William bought a grocery store in Kalona, a neighboring town, and together they co-managed it for eleven years. When they left that business, Edith worked at Pleasantview, the Mennonite-operated nursing home in Kalona. In 1980 she returned to school at a nearby community college and fulfilled an old dream to further her education. She became a certified medical aide and remained at Pleasantview until her retirement in December 1989.

Judged by most standards Edith Nisly did not have an unconventional work life. Due to her background, however, the time she worked off the family farm from 1935 to 1941 had a lasting impact on her. It was a new experience not only for her personally but also for her generation of Mennonite young people, who were used to the social isolation of their church community. Despite the daily drudgery of the job, Edith enjoyed the opportunity to meet new people, to try something different and to help her family in a time of need.

Her employment experience at the Maplecrest packing plant was not difficult as it only involved her time a few months of the year for seven years. In addition, it was easier for Edith and her sisters to leave their community for work because they knew the factory owner who, as a neighbor and fellow Mennonite, understood their work patterns and lifestyle. They could take off for farm work, leave early on Saturday, and never work on Sunday. They sacrificed nothing except their isolation.

Life changed for this Mennonite family when their daughters began to work at Maplecrest. Although they retained their traditional ties to church, community, farm and family, Edith and her sisters enlarged their contact with the world around them. The contacts did not change Edith’s views of the church or her relationship to her family, except perhaps to strengthen her appreciation of those ties; it did, however, alter her view of the world. She, along with her community, had to learn to deal with non-Mennonites. The result of this experience was the loss of social separation that meant so much to this church community. They had to learn to maintain their beliefs and community ties while learning to function in a continually broadening context.

NOTES

Hope Nisly is a graduate student in the departments of history and library science at the University of Maryland. Like her mother, she also grew up near Wellman, Iowa.

FOOTNOTES

1 Bob Godlove and Henry Wenger, “Maplecrest,” in Wellman Centennial Book: 1879-1979 (Wellman, Ia: Wellman Centennial Committee, 1979), pp. 72-73.

2 The Historic Peace Churches include the Mennonite Church, Quakers and the Church of the Brethren. In 1939 Congress passed the Burke-Wadsworth bill allowing conscientious objection on religious grounds. This granted members of the Historic Peace Churches exemption from participation in war and permitted them to perform alternative service in the Civilian Public Service.

“Nighthawks: Puzzling Through Life”

Pacific Journal, Fall 2013

Pacific Journal, Fall 2013

Nighthawks: Puzzling Through Life11

Order out of chaos – that’s what’s so deeply satisfying about piecing a jigsaw puzzle. If you look at my office, you’d think order wasn’t important to me. But at the jigsaw table I can achieve order. –Pamela Johnston

On a folding table in my dining room, taking up space that might be better served as a walkway or plain open space, are the scattered pieces to yet another jigsaw puzzle. This is one in a line of puzzles that I keep moving through its paces: turn all pieces right side up; sort out edge pieces and piece the border; and then, finally, begin work on the juicy core of the puzzle. I use the term “work” in the sense that it is a process, but not because it is a chore. Piecing a jigsaw puzzle is not hard labor, but rather a peaceful process.

This jigsaw puzzle, however, is more recalcitrant than most, if I may anthropomorphize it. The picture, while fascinating, is a bit drab and has a relatively limited palette. The process is complex and sluggish. And still I plod on in my quest for the satisfaction that comes when a piece finds its home and a picture emerges. This puzzle is Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. I like pictures and puzzles that let me look into other lives: the glow from someone’s kitchen at dusk; a hint of the conversational buzz emanating from a restaurant on a Paris street with the Eiffel tower in the background; or, as with my current puzzle, four lonely figures in a late-night, urban diner.

Appearances can be deceptive. This puzzle does not look particularly difficult, but I know, from my effort to put it together several years ago, that it is. With that attempt I did the unthinkable; I plowed my way through about eight-five percent of Nighthawks before I irritably dissembled it and returned it to its box. A jigsaw puzzle seldom stymies me. In this particular puzzle brand, however, too many pieces are so similar in shape that they appeared to fit when they do not. One wrong placement threw the entire process off balance, turned it into a struggle. I would finally concede that something was not right, lean in close to find the offending piece, and begin again. Finally, I became tired of the guesswork. No longer fun or relaxing, it became hard work. With several hundred pieces remaining, I quit. Nighthawks waited on the shelf until this year when I began to write this essay on jigsaw puzzling.

With my previous failure haunting me, I reopened Hopper, spread out the pieces, and assembled the border. I promised myself–and the three diners and the barman–that this time I would complete the puzzle if it took me all year to do it.

I have a fascination with words and with etymology, how words are put together. You might say that putting a jigsaw puzzle together is an extension of my love of words. – Pamela Johnston

For several years I have considered writing an essay on puzzles and puzzling. (Puzzling can be a verb, but usually in the terms of “her attitude puzzles me” and not “tonight I will be puzzling at home alone.” Even so, I use it as such.) The essay keeps nudging me, in part because jigsaw puzzles evoke intense memories.

Despite a slow start to the essay, I persist for numerous reasons. Puzzling gives me a warm sense of nostalgia for my siblings, my mother, and my childhood. In addition, I credit puzzles with holding my marriage together – my Swiss sense of time has always clashed with my husband’s attitude that “he’ll get there when he gets there” and puzzles often fill those interminable minutes that I spend waiting for him with increasing irritation. Jigsaws also sustained me through many sleepless nights when our teenage daughter would disappear for days at a time. Puzzles have been relaxation, therapy, meditation, companionship, and playfulness. But beyond those external issues, puzzles provide the intrinsic satisfaction that comes when a picture forms out of nothing more than a pile of colorful pieces of cardboard. Order from chaos; life pieced together from scraps of nothing. Where else could I find one lone activity that has functioned in so many ways in my life?

As I worked on the essay, I would jot down notes on slips of paper, later to transfer them to a word document. It kept growing until it was over ten pages, but it continued to meander aimlessly. I would write a little some afternoon, get discouraged when it did not flow easily, and put it aside. For some reason, the ideas simply did not transition well between concept and page.

Writing, which is usually a pleasure for me, became a chore. At the same time, my friend Susannah, a poet and novelist living in upstate New York, was sending me emails detailing the flowing of her own muses. She was finishing the third book of a trilogy set in the depression years on an Iowa farm. I read her drafts, garnered pertinent information from my parents (both were Iowa farmers in the Great Depression) to pass on to her, and kept hoping that this would help jump-start my own essay or, if necessary, give me permission to drop it altogether.

Discouraged, I would leave the essay and pursue other things: working on other stories, researching information on Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina for an upcoming vacation, watching episodes of The Wire, or hunting for a good recipe to make for dinner.

But the pieces of the essay remained scattered and vague. And then began my rerun of Nighthawks.

The two hardest puzzles I ever did were not large. They were each only five hundred pieces. One was called “Close-up of Three Bears” which was all brown; the other was “Close-up of Snow White” and it was all white. – Susannah Loiselle

As I laid out the pieces for Nighthawks, I remembered from my previous effort that, after the monochromatic edge, the next part was not so challenging. The interior of the puzzle contained several spots of bright contrast: the blue-white of the diner light spilling out onto the street, the yellow-white of the interior butting up against the mysterious dark surrounding it, the jade-green of the window ledge edging the bottom of the window. This contrast lends itself well to working a puzzle. At the outset, at least, I would not run into too many problems.

When I got to the people and urns, however, I ran into my first snag. The individual puzzle pieces refused to relinquish the requisite information that aids identification and placement. I could, however, begin with the most apparent lines of Nighthawk. The jade that delineates the bottom of the window soon reached a finger into the interior of the puzzle. In a touch of surprise, the easiest objects to cut from the herd are the stool tops hovering above the low window sill like UFOs in an Ed Wood film.

Each day, Doug watches my puzzle progress while he gets ready for work. Our morning rush to get out the door and on our way to work (on time), which used to be one of our points of contention, now provides a moment of meditative labor for me. I blithely do my puzzle and Doug can take as long as he likes to get ready. This morning, between breakfast and the shower, he tells me that the French word for jigsaw puzzle, Casse-tête, means “head-breaker”. Doug is fluent in English and German and he knows enough French to get by in Strasbourg, if not Paris. He has an endless fascination with word origins and meaning. “Head-breaker,” he repeats, “seems kind of appropriate for your puzzle.” I agree. It threatens to be a head-breaker even though I am momentarily satisfied.

I tell him that I know that this puzzle is going to be hard work. “I’m enjoying it, but I’m not sure I’ll still be saying that at the end of the week. That interior looks pretty foreboding. Not so playful.”

“Schiller talks about play,” Doug continues. “We read Wallenstein in high school and talked about his ideas. He says that play reveals a person’s true nature. But, if I remember right, he’s not talking about something like a jigsaw puzzle with a rigidly prescribed course of action. He’s talking about the play fullness of decision-making that comes before a specific path is chosen, points where there are options to consider and weigh.”

The mention of Schiller sends us to our German language bookshelves in the piano room. Doug grew up in Germany where he studied (and retained) many of the German classics. He did not read Hemingway or Baldwin or Fitzgerald, but we still have a shelf full of Schiller and Goethe, Bretano and Böll. He is certain that he has Wallenstein, but a perusal of the German shelf reveals only one Schiller, Don Carlos. There goes that part of the research–at least for now.

Even though assembling a jigsaw puzzle might be a prescribed process and even if Nighthawks is not relaxing, I plan to keep working on it to the glorious finale. Casse-tête or no casse-tête.

By this time, we are running late for work. Both Schiller and Hopper will have to wait.

We like a puzzle that is not too easy and not too difficult. We have learned that we do not like anything over 1000 pieces and not ones that are all the same color. But pretty hard is good. – Jill Miller

The piecing of Nighthawks continues in fitful starts and stops. The snags are constant; the times when it flows are far between. With less challenging puzzles, it is fun and satisfying to pick out a piece with a vase in the window, the tail of a dog, or a lawn chair on the far end of a beach. In Nighthawks, however, I cannot trust the details. Ears are not ears when isolated on a puzzle piece. Spigots are not quite spigots. A salt shaker is merely a splotch of white. I spot the woman’s face, but can find little of the rest of her. The men’s hats blend into the background with only a narrow ridge of light to help identify them.

There is a flourish of black on one particular puzzle piece that I keep trying to analyze; no matter which way I turn it I see the wing of a raven. For the life of me, I cannot determine what this shadow might be in the grand scheme of the diner. I know that there is no bird in this puzzle; I know I must alter my perspective, but my brain is doggedly persistent with this errant tidbit.

My mind is playing a game with me and there is nothing I can do. Perhaps this is where “play” comes into play. Much like Lewis Carroll plays with us in his tales of Alice or M.C. Escher twists our perception with unending stairways and paths, my mind toys with, and refuses to surrender, the image of a raven. What portion of the whole does this piece represent? My “bird’s wing” remains a bird’s wing until, a half hour later, the piece slips into place at the tip end of the diner window jutting into the pale blue-ish light of the street.

Nighthawks must be one of the most spoofed pieces of art. Everyone, it seems, takes a crack at playing with Hopper’s painting. It has been recreated in numerous movies such as Glengarry Glen Ross or Wim Wender’s The End of Violence. It has shown up in The Simpsons, with Eddie and Lou at the counter. A Simpson’s poster (not in any show) places Homer in the diner with a platter of doughnuts, sitting across from Chief Wiggums and Mrs. Krabapple. That 70s Show seats Red and Kitty in the diner. If you google “Michael Bedard Window Shopping” you’ll find Bedard’s painted parody of Nighthawks with an alligator scrutinizing ducks through the diner window. Poverino Peppino’s Boulevard of Broken Ducks parodies Bedard’s parody: he places the ducks outside eyeing the alligator in the diner.

If you google just “nighthawks parodies” you’ll find more parodies than you can imagine: Star Wars, the original crew at Christmas, Easter rabbits (Peeps) at the counter, Nightmuppets, aliens, Marilyn Monroe/James Dean/Humphrey Bogart, Breakfast Hawks (a place called Molly’s, of course), and zombies. There are more – so many artists and jokers playing with Nighthawks. Something about this painting intrigues us enough to toy with it endlessly.

And the painting intrigues me enough to make a second attempt at completing the jigsaw puzzle version of the painting.

What is funny about us is precisely that we take ourselves too seriously. – Reinhold Niebuhr22

Talk about Schiller and play piques my curiosity (a little) about the meaning of play– philosophically, theologically, or psychologically. A preliminary search in the research databases at the library brings up articles on Schiller, child psychology, sports, biology and play behavior in animals, and on Huizinga and Homo Ludens, to name just a few. That small foray into research satisfies my curiosity; this is not what interests me most. A trip down this path will take most of the fun out of both the essay and the puzzle.

I find, however, a reference to the “puzzle women” of Germany. I download an ebook by Anna Funder that details the lives of East Germans during the forty years of communist control. Employed by what is now called the Stasi File Authority, these women sit in rooms with bags of documents that the Stasi (East German secret police) shredded in the final days of their power. In the panic surrounding the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the ending of the regime, the officers burned, pulped, and shredded as much evidence as they could. When their frenzied efforts burned out all available shredders, they continued to rip the documents with bare hands.33 These documents were bagged, but they never made it to the landfill.

In a building near Nuremberg the puzzle women, as they are known, are slowly, painstakingly piecing these documents back together. They do it, one of them told Funder, for the satisfaction of providing the possibility of someone’s peace of mind: that this person might discover why s/he was fired from the university or what happened to a loved one.44 This monumental task could be accomplished by a computer program, but the original document is desired.

Funder describes their work as “something between a hobby farm for jigsaw enthusiasts and a sheltered workshop for obsessives.”55 Several of the women admitted that, even after a long week of piecing together documents, they go home and do jigsaw puzzles. Indeed, they approach the documents in much the same way that they would work a jigsaw puzzle. Utilizing clues from the paper weight, paper type, and the typeface or the handwriting, they find corner pieces and work their way into the center. By the most generous calculations, it would take these thirty-one workers almost four hundred years to piece together the documents in all fifteen thousand bags.66 Despite the odds, the “puzzle women” continue to reconstruct the lives of East Germans as recorded in the shredded Stasi documents.

And still they go home to work on jigsaw puzzles.

Oh ick. Jigsaw puzzles! How can you stand them? If you really need a hobby or something to kill time, knit an afghan or bake some cookies. Do something useful — or tasty. – Barbara Nisly

[Puzzling] is not work or play. It is contemplation and satisfaction. If it begins to feel like work and stops being fun I go away from it. I think of it like a Japanese tea ceremony: the cracking open of the box for the first time, the smell of the paper, the order that emerges. Even finding the right puzzle at the right time is part of the relaxation and contemplation. –Pamela Johnston

On the American Jigsaw Puzzle Society’s website, Daniel McAdam presents a brief history of jigsaw puzzles. He concludes with this defensive statement: “Jigsaw puzzles are a pastime, and I will make no nobler claim for them. But they are a healthier pastime than watching inane (and occasionally vulgar) television shows or playing inane (and occasionally vulgar and/or violent) computer games. And if they are addictive – and they are – they are a harmless addiction.”77

Puzzlers can be a bit defensive about their love of jigsaw puzzles. Perhaps that is because to non-puzzlers, the pastime appears meaningless. Perhaps it is a defense for a hobby that is neither work nor play, that does not accomplish anything useful or create a work of art, and that consists of a prescribed process with only one possible ending.

Doug tells me that he finds the process to be a bit annoying. “I spend my life looking for things: my lost keys or comb or glasses. Why would I want to spend my leisure time searching for little cardboard pieces of a puzzle?” He might be irritated by the process, but clearly, he is not upset by the fact that I have a puzzle on the table, interfering with our meals and bill paying sessions. To be sure, he is quite pleased that a puzzle helps me maintain my patience when he does not want to hurry or be hurried. More to the point, he views the persistence that it takes to piece a puzzle to be a tad pathological. I remind him that he can get downright persistent to the point of pathology when he decides, for example, to study the federal deficit or to scrutinize the hidden costs of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. “The pathology of persistence,” I tell him, “is all in the eyes of the beholder, is it not?”

I use puzzles a bit like the philosopher Hume approached games. He said that when he finds himself thoroughly confused and depressed by his musings on the meaning and nature of life he would “dispel these clouds” and cure his melancholy by dining or playing a game of backgammon. “… and when after three or four hours of amusement, I wou’d return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain’d, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.”88

Rather than defending jigsaw puzzles to their detractors (defense being useless in most arguments anyway) I will simply try to describe the satisfaction. I find it almost as difficult to describe the feeling that goes with puzzling as it is to complete Nighthawks. There is an intensely visceral nature to puzzling that draws me in, time after time. I love the feeling as a piece slips into the tessellated whole. (One positive characteristic of online jigsaw puzzles is that the designers often include a sound effect to enhance the “feeling” of placing a piece. It is a resoundingly delightful “clunk” that cannot be replicated in real life puzzling.) All satisfaction can be lost if the puzzle is cheaply made and does not fit together nicely. There are some brands I steadfastly refuse to buy; others that I buy no matter how schmaltzy the picture. I am looking for a certain feel and I will not settle for less.

As a general rule, I place the pieces by color and design; shape is secondary, although not inconsequential, to the process. I find a piece and examine the picture on the box to figure out where it goes. (And a curse on the puzzle company who puts its logo over any part of the face of the picture.) There is, at times, a risk in doing it this way. Sometimes what looks like a dog’s hind leg turns out to be a crack in the sidewalk; a horse’s mane is actually a tree branch; or a raven’s wing is really the edge of the window ledge.

Much like the proverbial lost coin, there is much joy when a long-hunted piece is located, when the picture is one step closer to its entirety. I relish the slow disappearance of the brown surface of my puzzle table as its surface is steadily replaced by an emerging photo or a painting. Sometimes I work by sections, sometimes I tackle a building, sometimes I hunt down all pieces in a specific range of the color wheel. When I need a challenge I begin with the most difficult segments of the puzzle and leave pieces of the house or barn (buildings being the easiest to reconstruct) for last. At times I try to form a single line of pieces between sections. When I want to slow things down (as I often do when I am nearing the end), I limit myself to the bottom four rows, insisting that all gaps must be completed in those rows before I go on to the sky or to the roosters beside the barn. But most often, I just have fun and work the puzzle in a free-flowing, organic way–whatever makes me feel good at that moment.

Doug tells me that what he does not like about a puzzle is that there is nothing open-ended about it. “There is one piece that fits in one place and you can’t creatively rearrange those pieces,” he states. That may be true, but the process is still mine to do in any way that I prefer.

I will not defend puzzles or pit them against television shows or video games or even reading, but I will say this: puzzling is release from the stress of life, a sanctuary without going on a retreat. Like Schiller’s idea of play, it is in puzzling where I reclaim my true nature. In puzzling I have all the patience and perseverance that I so sorely need in life, calmness in large portions, a playful spirit that I do not always reveal to the world around me. I am confident and happy to be here, ready to face the worst of days and most difficult people.

Omnia apud me mathematica fiunt. (With me, everything turns into mathematics.) – Rene Descartes in Discours de la Méthode. 1637

Perhaps watching me struggle with Nighthawks brings out the empathy in Doug. Or perhaps he is just tired of the puzzle. Most likely, he thinks he is amusing. Tonight, over biryani and aloo gobi at The Curry House, he tells me that because this puzzle is so difficult, perhaps I could try a different approach. I concede that traditional approaches have not worked well and I might want to look for another way.

“My idea is this,” Doug continues. “Because Nighthawks provides so few visual clues for placement, why don’t you try a mathematical approach? All you have to do is figure out how many pieces need to be tried in any given open spot. It might be less than desirable, but what do you have to lose?”

My blank look prompts Doug to reassure me that it would get easier with each placement. “But isn’t that how it always is,” I reply? “With each placement I have one less option for the next space–and that goes for either calculating it mathematically or just doing it. The calculations just make it take longer.”

“Yes, but it would give you a clue to how long it will take to complete the puzzle,” he continues. “With 1000 pieces, the first one has not only 999 other pieces, but several ways to place each one.”

I remind him that I already have about one-quarter of the pieces placed so we do not need to start at the beginning. “Let’s just keep it at 1000,” he tells me. “Easier to figure that way. It’s just 999 x 1000 / 2.”

I like math problems, but not when it interrupts my puzzle or my curry. Now if we could find a way to work this into a geometrical problem, I might be interested, but I am less sure about delving into statistical probability.

“We all know…” Any statement from Doug that begins with those three words usually denotes the polar opposite for me. He continues, “We all know that there are half a million tries to make and four rotations for each attempt. Of course, that’s if you’re extremely unlucky.”

“Unlucky?”

“Of course,” he continues. “The chance that you’ll have to try all 999 tiles is extremely unlikely. Now we’re working in the realm of statistical unlikelihood. And each successive time you could not possibly choose every single wrong piece before you find the correct one. So the equation is theoretically the sum of all numbers from 1 to 1000 (1 plus 2 plus 3, etc.) But it would never be how it works in a real life.”

Sometimes I enjoy these theoretical/mathematical conundrums, but tonight I want to savor my curry and rest my brain. There may be people who find a mathematical approach playful and scintillating. I am okay with it at the theoretical level, but when it comes to my puzzle it merely make my brain hurt. I suggest we drop this approach and move on to something else. Like the biryani.

Doug says fine and that he was just trying to help. We finish off the meal with kolfi and head off to the evening’s harpsichord concert.

I like it when you do puzzles; you’re never as anxious about time when you have a puzzle on the table. – Douglas Kliewer

It is no small surprise that, in the history of jigsaw puzzles, the times when puzzles sold at the heaviest rate were during times of national anxiety. The first puzzle craze began during the 1907 recession and Bankers’ Panic. Prior to that, puzzles were mostly small and made for children. The recession precipitated a change and adults began to do jigsaw puzzles for the first time. Even financier J.P. Morgan (blamed and credited with both precipitating the recession and fixing it) and President Roosevelt joined in this national obsession.99 Again during the first years of the Great Depression of the 1930s, puzzle sales spiked. Aided by a simultaneous manufacturing change where jigsaw companies could mass produce puzzles at a much cheaper price, people across the United States took up jigsaw puzzles with a passion. Libraries even began to loan jigsaw puzzles along with books.1010

My mother, who grew up doing puzzles during the depression with her family, used this stress-reducing method when raising her children in the 1950s and 1960s. With a puzzle she could take her mind off the constant financial problems precipitated by the changing winds of farm markets, while simultaneously keeping her children entertained. For most of the year, my mother was a relatively unflappable woman. Along about January, however, even she began to look a little frazzled and crazy-eyed. In a blustery Iowa winter, one could not have, as she did, eight children in a three-bedroom house that was heated only on the first floor and not go a little stir crazy. There is a limit to the number of times you can send your children outside to play when the temperature hovers at ten below zero.

When the bickering began, she would gather us at the front door with instructions to stand outside and take deep breaths of the frigid air. When we straggled back inside shivering and gasping for breath, she would say, “There. Now that you got rid of all that stale air in your lungs, perhaps you can settle down and put a jigsaw puzzle together.”

And so our jigsaw marathon would begin. After we pieced all our puzzles, Mom would trade with her sisters and we would begin again. Those five hundred piece Whitman Guild jigsaw puzzles with their banal scenes relieved our boredom and helped us skate happily through the icy winters of childhood.

Or, perhaps more accurately, they helped Mom get through our winter boredom.

Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life. – Pablo Picasso

The paintings on the puzzles we put together as children (in the 1950s and 1960s) were of the bucolic sort and it would take a stretch of the imagination to call them art: villages in the Alps, fields full of corn shocks, lakes in national parks, English gardens, the village smith at work, deer standing at the edge of a woods. In reflection of the post-war zeitgeist and self-perception of many middle-class, white Americans, the scenes oozed tranquility.

In the upheaval of the 1960s, puzzles began to change. Jigsaw companies did not halt the production of tranquil puzzle scenes, but their new creations moved far beyond traditional halcyon landscapes. They, too, tried to keep pace with the pop art scene and the mass culture of the time. In homes across the country, it became cool to spread out puzzles consisting of hundreds of bars of chocolate, a sea of pennies, thousands of lady bugs, or sea shells from frame to frame. The truly pop art-ish ones featured different puzzle shapes; square was just too – yes, square. One Christmas, Mom’s friend gave her a puzzle of a tennis court seen from the air; it was entirely green with a few white lines.

In 1964, Springbok made the first move to new shapes – round and octagonal. Within the following year, Springbok’s owners, Katie and Bob Lewin, came up with the idea for fine art jigsaws and created a puzzle from Jackson Pollock’s Convergence. This change, as inconsequential as jigsaw puzzles might seem, was duly noted in Time and Business Week.1111 The Lewins began to search through museums and shops in a quest for anything that they could use in puzzle designs. Everything was fair game: peacock’s feathers, dice, colorful marbles, astronomy charts, and Kabuki embroidery. They even managed to convince Salvador Dali to create an image just for Springbok. He created a work that included scattered “missing pieces” painted across its face.1212

With this knowledge, I google “vintage Springbok puzzles” and find two puzzles for sale: “Millefiori Paperweight” and “The Language of Computers.” Both are round and evoke the 1960s. When I google “Dali Springbok 1965,” I find his commissioned work; I am not sure it is one I would want to piece.

At the time, my mom, my siblings and I delighted in these new-fangled puzzles. The old scenery was yawn-inducing and out-of-style. While I have once again come to enjoy some images and styles of earlier years, I am afraid that I can never quite bring myself to piece together a Kincaid scene. It is just too warm and fuzzy.

Weathered faces lined in pain, All soothed beneath the artist’s loving hand. — Don McLean (“Starry, Starry Night”)

Several years ago I put together only puzzles of fine art paintings: Vermeer’s The Art of Painting, Bruegel the Elder’s Children’s Games, Heironymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, Dali’s Persistence of Memory. That was the same year I first attempted to do Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. For a truly eerie experience, try piecing a puzzle of a Bosch masterpiece where you can examine each square inch of the painting, scrutinizing every weird little creature. Bruegel’s Children’s Games only fares slightly better in close detail. Not all of the activities of those little medieval children at play appear to be innocent and pure!