50 Give or Take, May 9, 2025 A pastor and social activist for his lifetime,…

“The Things He Read”

The Mojave River Review, Spring-Summer 2018

Without obsession, life is nothing. -John Waters

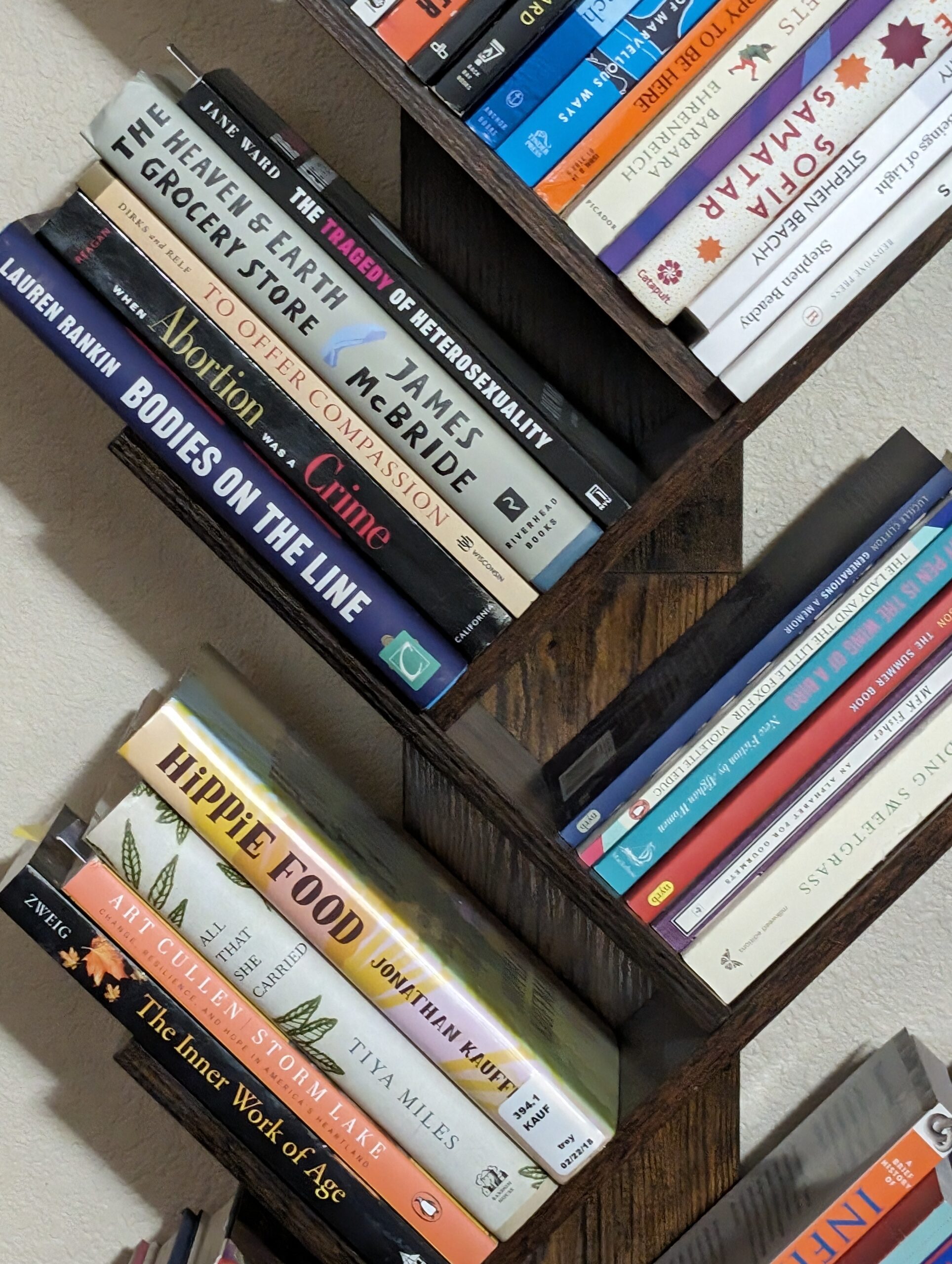

To be honest, he could never really say that he enjoyed reading, but he always knew that he liked what reading provided: information, adventure, and once even a BB gun. The gun was a parental incentive to read the entire Bible the year he turned ten. The reward was tantalizing enough to persevere from Genesis through Revelation. Other than Goliath and the psychedelic creatures of Revelation, he remembered little from this effort.

His parents bought The World Book Encyclopedia from a traveling salesman and he worked through all twenty-six volumes with much more verve than he mustered for his trek through the Bible.

His second-grade classroom included a four-volume science compendium that covered everything from space to electronics to weather. He read it so often that when his family moved, his teacher gave it to him saying that he read it more than all her students from the past ten years combined.

With the move, he had to learn a new language. Adults assured him that he’d learn quickly because he was young. It was a lie. He became the class clown and was spanked by his teacher for what they termed his “lack of effort.” (In those days, corporal punishment was meted out in near-biblical proportions.) He read only what he had to at school and continued to scour his beloved science compendium at home.

When he began to play piano, he read musical scores and the biographies of composers in German and English.

His mother’s friend sent a box of Scholastic books so that he could read in English. Unfortunately, she chose sports stories such as Break for the Basket which she thought all young boys liked. In fact, he hated sports and disliked those books. The science compendium continued to be his lifeline.

In high school he read German classics: Goethe, Brecht, Mann, Musil, Grimmelshausen, whose stories often chronicled the Thirty Years War from the varied perspectives of either the mentally challenged or the elite of society. They were gruesome, but mostly worthwhile.

Returning to the United States for college, he studied mathematics and music performance hoping he wouldn’t have to read much. When everyone around him lauded The Screwtape Letters he tried to read it. He not only did not finish it, he never got beyond the first five pages. This was one of the rare times when he did not compulsively finish whatever book he began. C. S. Lewis was not to his taste.

Upon graduation he moved to Berkeley where he worked for minimum wage in an electronics store. In the evening, he made simple meals (pasta, lentils) then spent evenings reading the dictionary through as if it were a novel in single words, each definition a micro-story. On Sunday mornings, he added the newspaper to his repertoire, for news and the want ads.

With the advent of the internet, he became an online news junkie reading four or five newspapers and Der Spiegel every day. Where other middle-aged men might succumb to porn, he yielded to the allure of information and politics.

In late middle-age, after reading Divine Comedy, he tackled Ulysses. This took him seven years, which, he liked to point out, was the amount of time it took Joyce to write it. When he talked about re-reading it, certain that he missed too much in the first go-round, his wife threatened to destroy his copy.

After Ulysses he read through the holy books of major world religions, beginning with the Qur’an. He discovered that, alone among sacred texts, the Book of Mormon was too tedious to bear. He harbors grudging admiration for the zealots who claim to have read it. This was the second (and last) book that he started and did not finish.

He continued to scour websites for news and politics while playing piano to get away from what he saw as the total insanity of the post-9/11 craziness of a homeland-secured world. When his son wrote from prison that he was reading the dictionary, he wondered if he had done his job of parenting well—or poorly.

He never learned to love reading. But, as always, he liked what it gave him: a feeling of accomplishment, information, and insight. He often wished he had kept that science set from his youth. Of all the things he ever perused, that was most meaningful.

And after the BB gun he owned as a kid, he never purchased or held a gun again in his life. Yet one more benefit to add to the list of the benefits of reading, however reluctant.