50 Give or Take, May 9, 2025 A pastor and social activist for his lifetime,…

“Reading to Unit H”

The Fredericksburg Literary and Art Review, v.6, #1, Spring/Summer 2018

I push the buzzer and wait for the click that let’s me know I can open the heavy-framed, locked door. The click is so faint, however, that I miss it (as usual) and I am forced to wait a minute before I can try again.

Not knowing what force monitors this door, all I can do is turn subserviently toward the camera to reveal my badge with reads “Probation Department, County of Fresno, Volunteer.” I picture someone watching me with a bit of malevolent, power-driven glee, making sure that I must try a second time. Even in the absence of an actual evil chortle I get a shivery surge of impatience, mixed with anxiety when I stand here. My mind’s picture, is of course, made up but no less real for being a figment of my imagination.

This is the most daunting part of my bi-monthly visits to Unit H of Juvenile Hall. The clanking thud of doors swinging shut and locking behind me is bad enough, but this anticipation of the nearly-imperceptible click makes me want to turn and run. It is only when I am through the door and on the ward with the boys that I can relax.

It is 9 p.m. on a Wednesday night and I am here to read to the boys of Unit H. The boys in this unit are the youngest ones in Juvenile Hall. When I went for an orientation session, the activity director gave me a choice: girls, ages 13-18; boys, ages 13-18; or the youngest ward, the pre-teen boys.

“Do you have many kids,” I ask, “who are younger than 13?”

“Lots!” She laughed at my question. “We’ve had them as young as 7.”

While I absorbed this surprising bit of information, she continued, “Some are in legal trouble, of course. Others are here because their family tells us that their kid is out of control and they don’t know what else to do. Some are good kids who just need a little discipline. Others,” she paused and shuddered, “they’re just … evil.”

My discomfort with her description must have been visible because she continued emphatically, “I mean it! Some are just bad kids. Like that movie … what’s it called? Bad Seed.”

Thinking of my own son who spent some time here, I wondered what kind of training is required to work here.

As I enter the visitation room of Unit H, I say hi to the three boys who are cleaning this common area. All three smile at me and continue to work at breakneck speed. The rest of the boys are already in bed. By the time I check in with the desk attendant and am ready to walk onto the ward, these three boys will be finished mopping and will bring their buckets and mops onto the ward, where they will mop between beds and around me, while I walk the floor juggling book and flashlight. Tonight I’ll read from Call it Courage, a book that held their attention last time.

A night attendant greets me then hollers to the boys, “Reading lady is here. Everyone quiet.” For better or worse, that’s how I’m known here: Reading Lady.

These boys have to be here. They have to be quiet and listen while I read bedtime stories to these pre-teenagers whose temporary home is Juvenile Hall.

I make a modest attempt to interact with them before I begin to read. I say hello and ask if there was anything special about their day. I follow it with, “Who remembers what we were reading last time?” There is a chorus in response telling me that many of them have been here at least two weeks.

One boy calls out, “Ma’am? Last time I was here you were reading Holes. Why aren’t you still reading Holes?” It has been a year since I finished Holes, which means this is at least his second round through Juvenile Hall. I tell him that we’ve moved on to another book and he groans his disappointment, finishing with, “I loved Holes.” I know. Even the attendants liked when I read Holes.

I open Call it Courage, while their voices float out of the darkness with details from the last time. “Mafatu killed the wild boar just before it attacked him.” And “Yeah! I remember. Wasn’t he in the water?”

This is the moment that I love, the reason I am here reading to these young boys who have transgressed in some way against the community or their family.

*****

Reading with my son Matthew always was an adventure, the part of parenting that I loved the most, the part of the day that he, too, relished. No matter what happened during the day, reading was our moment of respite. Bedtime stories slowed our chaotic days to a contented crawl. In a way, Matthew is part of the reason why I am here now, reading to the boys of Unit H.

Life with Matthew has always been journey of exploration, of hope, and (at times) of the loss of hope. As I am reading here to Unit H, he is in a prison over 1000 miles from here. His letters are long and neatly penciled, at times terse and full of information, at other times rambling with dreams and desires. From time to time, he reassures me, “It’s not so bad in here. No one is raping or beating anyone.” Although that is not my greatest fear, it is how he believes outsiders view prison life, harvested from scenes in movies or TV shows. In one particularly pensive missive, he ruminated, “People aren’t meant to live this way, penned up and with so little light.”

In his latest letter, he wrote, “I got a letter from Uncle Wendell. He said I should visit when I get out. Why would he want me to visit? He knows what I’ve done. Why would he want that? I’ll never get this about family.”

Even at it’s best, family can be fragile. Both Matthew and his sister spent years in foster care, so for them (and by default, also for me) family hangs by an even thinner thread. The process of parenting vulnerable children has made me acutely attuned to the minute nuances of familial dynamics and the rougher edges of life, to what it is that creates the differences that divide and the love that unites.

My children hold in their bodies the most intimate knowledge of how easily family is damaged, how difficult to repair. My childhood on an Iowa farm with a loving Mennonite family did not prepare me for some parts of this new recognition. I am grateful for the foundation that my family provided, the hope that people can live together in a broken and hurting world. Over time, I have come to understand just how illogical it is for Matthew to believe that family might be able to embrace him—even in prison. I can only hope that one day, he will not only believe it, but feel it deep within himself.

With personal histories of pacifism my husband Douglas and I intended to maintain a family structure that breathed nonviolence and love. Our emerging family, however, holds a self-definition of the most extreme turbulence. This was their story, but now it is part of our story. We tried to live our beliefs without excessive preaching, but our children (with their own brand of street wisdom) doubted it, doggedly pointed out our flaws in living it, and occasionally were fascinated by it despite their skepticism. Life had demonstrated the impossibility of peace. They expended a tiring and unbelievable amount of energy attempting to re-create the familiarity of violence.

In spite of my best intentions, I acquiesced to my own inner violence more times than I care to admit, while we set out to demonstrate that family lasts forever and nonviolence is possible. With a family narrative rife with chaos, the intimacy of daily life counteracted our best efforts. So, in the colloquialism of our bumper-sticker culture, “Shit Happens.” But love grew anyway, flying in the face of our efforts to prove anything. And that, ultimately, is the best definition that I have for “nonviolence” or for “family.”

It is within this framework, nestled within our attempts to care for each other and failing often, that bedtime stories became our keystone to family life and peace. In those moments, chaos could subside, if only for a brief window, and we began to shape a new story together. We lost ourselves to this emerging family landscape. It may have resembled a Salvador Dali scene rather than a Norman Rockwell family. But it was ours and it was good.

While we read, Matthew changed from an 8-year old who could not sit still through a picture book to a 10-year old who understood the complexity of Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. My son, this wiry little boy who nearly burned our house down, who kicked out the porch posts in anger, was the same child who came to love farm stories and time travel and historical fiction and, really, almost anything.

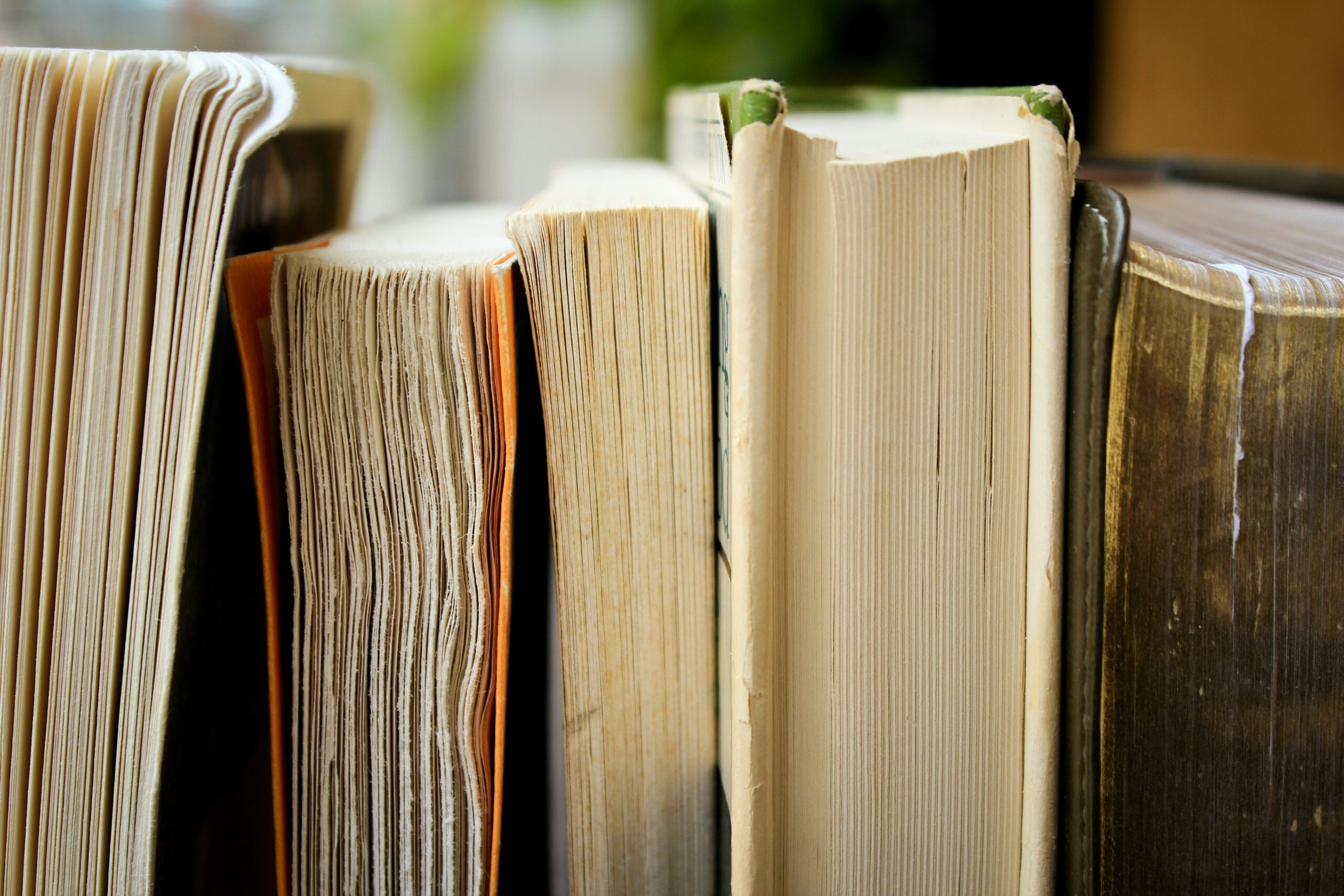

Books anchored us. So when I say that I believe in the power of story, in the possibility of nonviolence, and in the permanence of family, it is not merely an idle cliché. It comes from a place deep inside where I know that the impossible is within reach, if only for a few minutes at bedtime.

*****

As I enter Unit H, I notice the nurse. A boy stands beside the nurse’s medicine cart, shaking and crying. The nurse addresses him by his last name. “Now Mr. Jackson,” he says gently, “I can’t give you sleeping pills. But I have a Tylenol for your headache. Mr. Jackson … can you look at me?”

The boy doesn’t look up and the nurse repeats, “Mr. Jackson?” The boy reluctantly lifts his tear-streaked face. The nurse tries to get him to relax by wiggling his arms at his side, but the child is stiff with fear. He sobs quietly, “I want to go home.”

The night attendant asks me to wait a moment while he quiets the boys. Evidently, it is not just “Mr. Jackson” who is agitated tonight. “Must be the full moon,” the attendant laughs, but his chuckle reflects little humor.

At times, I doubt the value of reading bedtime stories to the boys of Unit H. I volunteered, quite honestly, for my own satisfaction. I don’t believe it will change lives. Often, I am unsure that they even want this story hour. My stories are simply another thing inflicted upon them by a world of adults with inordinate power over them. If I really hoped to make a difference, there might be better options available. This, however, is what I do twice a month, forty minutes a night. I read bedtime stories to the youngest boys of Juvenile Hall.

I begin to read while I balance the book and the flashlight, walking the length of the ward and back again. Projecting my all-too-quiet voice reminds me of my limitations here. Some boys are uninterested. It won’t change their lives. Many will return to Juvenile Hall more than once, perpetrators of crimes and blinded to possibilities in their worlds of violence. And too often, all we see when we look at them are “bad seeds.”

After I finish the next several chapters of Call It Courage, I make my usual final sweep of the ward, saying good night to any boy who is still awake. I promise to return with more of Mafatu’s story in several weeks. I hear a few snores, some quiet “goodnight ma’ams,” a thank you or two. In this moment, as I round the ward I see, not troubled young boys, but innocent children who love a good bedtime story.

As I get to the door and begin to move into the light of the staff station, I hear a whisper near my head, “Thank you for reading to me tonight.” I turn to the bed on my right. On the top bunk beside me, I see the teary-eyed face of “Mr. Jackson.” Whispering good night, I add, “Sweet dreams.” He repeats his thank you and lays his head back down on the pillow.

*****

When I told Matthew that I am reading to Unit H, he reminded me of a few books we had shared. “Don’t forget Harris and Me,” he prompted. “That was one of the best ones.”

As a child, Matthew struggled to read. Testing revealed no learning disabilities. Finally, one consultant explained how external trauma can prohibit the transferal of learning from short-term to long-term memory. In essence, each time he read, he was re-learning how to read. As difficult as it was, he loved to learn and loved to be read to. For a time, he even wanted to become a writer, encouraged by a teacher who said he had a knack for understanding the format and arc of a story.

He asked me to send books to the prison library. In his first months there, he had perused the entire prison collection, a bunch of old National Geographic magazines, plus a few mystery and spy novels. I spent an afternoon at bookstore, carefully selecting a box of books to send. I took his suggestion (science fiction) and added a few more: Orson Scott Card, Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a Philip K. Dick novel about time flowing backward, Stephen King’s On Writing, plus a few more.

While I browsed, I thought of Matthew, but I also thought of other inmates, men I will never know, who would also have access to these books. Could a good book in a prison library point the way toward unimagined and unimaginable possibilities? I have no way of knowing.

When the prison received the box, Matthew called to thank me. His cell-mate, Milky, sent his thanks, too. As it turned out, Milky loved to read. When Matthew told him how difficult he finds reading, Milky offered to read to him. By the time he called me, they had already finished several books.

I, personally, don’t know how to define and live words like “family” and “nonviolence.” Society, collectively, stumbles over “justice” and “equality.” The fluidity of life, along with variables of class, culture, ethnicity, and gender often render definitions inadequate.

Life experiences have rearranged my hopes, just as they have limited my children’s dreams. I see the (rotting) fruit of violence in their own lives and how they have come to live beyond it into a world of light. I am convinced more than ever that nonviolence is necessary, whatever it’s limitations.

Mostly, however, I picture Matthew and Milky in a prison cell, reading out loud to each other. It may not change things to the degree that I would like just as my reading to the boys of Unit H will not alter their circumstances. Still, it lulls me to sleep at night, this image of two young men who defy society’s stereotypes by one seemingly-insignificant, yet remarkable act—they read to each other.