“Ages and Ages Hence: A Conservative Mennonite Woman’s Secret Dreams of Education”

Journal of Mennonite Writing, v. 9, 2017

“This I remember. How happy I was to be there.” – Edith Swartzendruber Nisly (1919-2017)

The dream came to her soon after she turned ninety and she called to tell me about it. She laughed as she spoke, but it was more tentative than her usual deep-seated laughter.

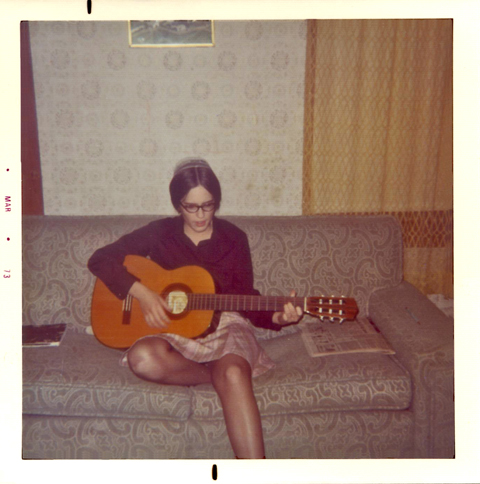

I was nearly the youngest of a large family and born when my mother1 was close to forty; I had a relaxed relationship with her. She was past the general chaos that came with a profusion of young children in a too-small house, past the point she worried over other people’s opinions. So we laughed together, relaxed over meals, shared our day’s events. With little hesitation, she told her hopes, freely admitted to her mistakes. To be sure, we also clashed over curfews and hemlines and hairstyles. It was, after all, the late 60s and early 70s.

So now my ninety-plus-year-old mother tells me her dream, which we didn’t know at the time would be a recurring one over the next several years. “I’m going to college. I was at Hesston. And there I was, an old woman trying to keep up with the young people. I couldn’t find my class or my notebook, but I was happy to be there,” she smiles. “This I remember. How happy I was to be there.” Then she finishes with another chuckle, “It’s sort of silly, isn’t it? I just don’t know why I would be dreaming this.”

Now her voice gets a little lilt, full of the amusement that I remember from my teenaged years when we were playing Scrabble and she was about to lay a risqué word. “I had plans you know,” she continues. “There are things I’ve never told anyone before.”

I wait while she pauses. Sighs. In the background I can hear the call bells that are an integral part of nursing home life. Through the phone and across the miles, I can almost hear her smile.

2. Layers of Identity

When I signed up for the pre-medical course I wasn’t at all sure what the folks would think of my ideas. I didn’t want to ask Dad point-blank. He would be honor-bound to raise reasonable objections. … I told him I was in pre-med but that there were many applicants for entrance … and not nearly all were accepted and especially not if you were a girl. Dad ate a few bites and then he said, “I guess you’re as good as anybody.” And that was all he ever said. He gave me the same support and co-signed notes at the bank the same as he did for his sons.

– Lydia Hershberger Emery (1909-1997)

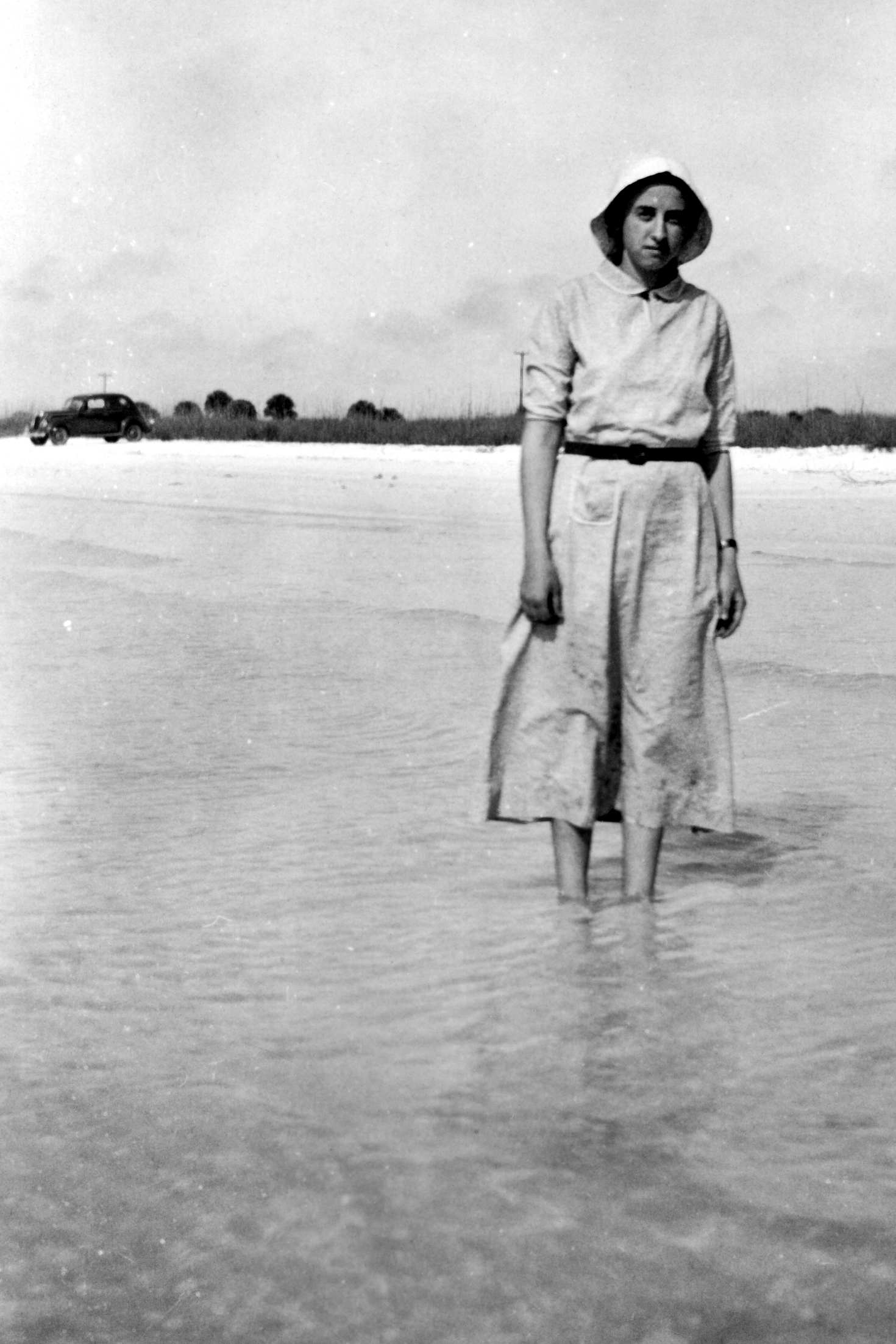

My mother, Edith Swartzendruber, was ten years younger than her father’s cousin, Lydia Hershberger. The two women were from the same rural community, both were Mennonite. In 1934, Edith attended 9th grade (over the protest of her church) and then was forced to quit school. At about the same time, Lydia matriculated into a pre-med program at the University of Iowa, a state institution near the Hershberger and Swartzendruber farmsteads. She graduated in 1941.

In later reflections on her decision, Lydia acknowledged that, initially, she told no one. “When I signed up for the pre-medical course, I wasn’t at all sure what the folks would think . . . I well knew confrontation was not the way to go; not when dealing with a Hershberger and a good Mennonite father.” She waited for her acceptance letter before telling her parents. If they entertained any doubt about their daughter’s choice, they concealed it and offered financial support.

In the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, American society did not believe that women should be educated. Even those who advocated for women’s education cared less about equality and justice, and more the creation of a democratic society. Educated mothers were a necessity to prepare sons for civic duty in a democratic society.

In Iowa, where Edith grew up, the story of women and education is unique. In 1855, the state founded the first public university in the U.S. that accepted white women and men on an equal basis. This is not to say that Iowa women desiring an education had smooth sailing. A few years later, the Board of Trustees attempted to create a separate college for women, but faculty thwarted that effort.

In the 1930s, eighty years after the first women entered the U of I classrooms, Edith’s cousin Lydia still worried about getting into the program. “I told [Dad] I was [trying for] pre-med but that there were many applicants … and not nearly all were accepted and especially not if you were a girl.” [Italics are mine.]

A multiplicity of identities shaped Edith. She was part of the Swartzendruber family, she was a Mennonite child, and she was the daughter of a revered bishop. She was born a year before the ratification of the nineteenth amendment granted voting rights to women and came of age during the Great Depression. She was a Midwesterner, an Iowan, a farm girl who attended a one-room school. She grew up seven miles from the closest town, thirty miles from the nearest city. Her family belonged to a congregation that broke away from the Mennonite church so that it could better resist assimilation into American society and culture. It rejected education for its young people, whether male or female.

In her later years, my mother told me how the county superintendent of schools came to her home in the month before she would finish ninth grade. She listened to the conversation through the heating grate in the floor of her room while the adults discussed her future. She heard him tell her parents that their daughter was a good student and a ready learner. “You should really let her finish high school,” he told them. This superintendent had promoted Edith from third to fifth grade, a common practice for students who surpassed expectations.

Her father wanted his daughter to finish high school. He was, in fact, the bishop and if he decided to forge ahead, he had the authority to do so. But, as a committed Mennonite, he also believed in the authority of the congregation, the collective wisdom of the community. The community (gemeinschaft) and submission to the communal decision (gelassenheit) took precedence over individual desires. Edith’s father believed it would be an abuse of his power to override the congregation’s concerns about education. He did, however, insist that his daughter would finish the ninth grade, over some protests.

Edith and her older cousin, Lydia, were born in the same milieu. Both were Iowans, farm daughters, and Mennonites. Each assessed their situation and then followed two different paths. Knowing that support from family and church was not guaranteed, Lydia chose to become a doctor. Edith chose to adhere to the communal decision of her church. To defy the church’s boundaries, to rebel against its restrictions would have cost her more than she was willing to risk, even with the knowledge that either decision would result in a loss to herself.

More Dreams

I had plans, you know. Did I ever tell you that part?

-Edith Swartzendruber Nisly

“I always told people I wanted to be a nurse.” My mother is now 94 and she’s had numerous dreams about attending college. In them she has been to Hesston, Eastern Mennonite, the University of Iowa, and a local community college. With each dream she reveals a bit more.

“I knew it would be acceptable to say I wanted to be a nurse, but it wasn’t what I really wanted.”

When she continues, her speech has slowed. I hold my breath. I don’t want even the faintest sound make her reconsider her desire to talk. But age and time seem to have removed her fears.

“I really wanted to study mathematics,” she continues. “I had plans, you know. Did I ever tell you that part?”

“Also,” she pauses, “I never said this before, but this dream reminded me of my secret plans to run away and enroll at Eastern Mennonite School.”

In this Depression-era Conservative Mennonite community, it would have been a risk to admit out loud that a young woman wanted to study mathematics, that she enjoyed studying and wanted more education. It would have set one adrift in ways that I can only faintly imagine. Edith understood the implications, maintaining a stoic silence until her nonagenarian dreams reminded her.

There were those Mennonite women who found ways to get an education. In a 1983 book Mennonite Women, 1683-1983, Elaine Sommers Rich profiled women who obtained a college degree, one as early as 1896. Some, as might be expected, studied home economics or English, but there were also women learning French, Latin, Greek, and mathematics.

In 1925, John Hartzler wrote about the traditional reasons that Mennonites in the United States shunned education. He wrote of their suspicion of the state and its institutions, of their fear of worldliness, and of the rural, isolationist nature of most Mennonite communities. “Higher education,” Hartzler wrote, “appeared to them as full of worldliness, pride, boasting …” But he also went on to say that the upcoming generation was losing those fears. When he wrote this, Mennonites in the United States had already founded seven colleges.

My mother’s particular community of Conservative Mennonite congregations was not, as Hartzler wrote, “losing its suspicion of education.” It still believed that education led a person to abandon the faith.

The advent of her dreams provided my mother with the relief of revelation. When I told her that I wanted to write her story she was pleased. As I finished each section I would read it to her. When I got to the part where she related her plans to go to EMS, she sat quietly before asking, “Did I really use the term ‘run away’?” I assured her that she had.

“That sounds a bit strong, doesn’t it?” she reflected. “But it is exactly what I meant. I think I need to add something, though. I was too afraid to run away. If I would have had someone who wanted to go with me, who encouraged me, perhaps I could have done it. But I was much too frightened to go alone.”

Remembering, Reflecting, Resisting

I shall be telling this with a sigh,

Somewhere ages and ages hence…

-Robert Frost

In January of this year, several months before her 98th birthday, my mother died. As our family talked about her life before the funeral service, my oldest sister mentioned how Mom wanted to be a nurse. In my eulogy I told instead, the story of Mom’s hidden desire to study mathematics, something that surprised all but a few of us.

As a teenager, she had stood at a moment of decision. Knowing that she would lose her community and her support system if she chose to get an education, my mother was unable to factor in her loss by choosing against personal calling, desire, and gifts. Choosing the path of community, she married and raised a family, chaired the sewing circle when asked, and occasionally gave her testimony or read her essays during the Sunday evening Young People’s Meeting (the one space allocated for women’s participation in the public life of the church).

At sixteen she acquiesced in silence. She experienced a fleeting moment of inner rebellion with her plans to run away, but an open admission to those plans could only happen eight decades hence. In her thirties, she discouraged her oldest children from education, utilizing the very words that she had once strained against: “You will leave your faith if you do this.” In her forties, she began to reveal her youthful desire, but couched it in acceptable terms: “I wanted to be a nurse.” Nearing 50, with most of her children grown, she took classes at a local community college, getting a certificate to be a medical aide. Nearing 60, when I told her that several women at church warned me against college, she looked me in the eye and said clearly, “Pay no attention. You’ll regret it if you don’t go.” It was years before I grasped the full import of her advice. Finally, in her 90s she began to reveal the fullness of her youthful desire.

Through all her stages of life, she practiced small forms of resistance: she shared infant and child care with her husband, a move that was out of the ordinary in the 1940s; she taught her sons to cook, stating that her sons would not go into life or marriage without knowing their way around a kitchen; when another child at church taunted me with, “your mother has to work” she merely laughed. “Tell them that I’m doing exactly what I want to be doing.” In time, she took courses at the local college.

Those things (teaching sons to cook, sharing child care with her husband, working away from home, getting a community college certificate) are not particularly earth-shattering until you put it in the context of her life and times. It is true that she did not follow her dramatic route of running away, but she found small ways over the intervening years to follow her own path. To see her life as quiet acquiescence would be, I believe, yet another loss, one that would compound the losses already present in her life.

So if she only resisted in the most oblique ways, if she encountered her communal boundary and could not cross it, because she chose the loss of education over the loss of community, why tell her story at all? A life story such as that of my mother is difficult to come by, but it is illustrative of the lives of women who cannot tell their stories, who suppressed or forgot them, who could neither find the words to articulate their story nor the courage to resist their strictures in even the smallest of ways. It is those stories that concern me, stories that seem insignificant at first blush, stories that are less likely to be told than the stories of women who found the courage to hurdle their barriers.

As Brenda Brasher said in her book on fundamentalist women, “… it is difficult for such stories to survive, even as gossip. They sink like stones out of the claimed visible memory of congregational life.”

I want my mother’s story to survive, not only as a poignant story for myself, but as a window into a world of barriers and fears that women faced, and as a revelation of the subtle resistance of countless other women as well.

https://mennonitewriting.org/journal/9/4/ages-and-ages-hence-conservative-mennonite-womans-/